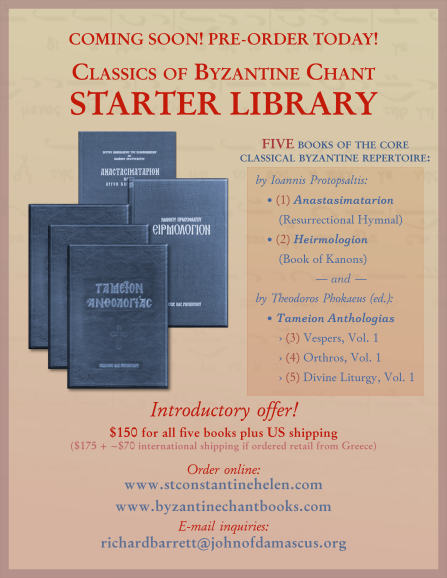

There’s a story here to be told another time, but this is another venture I’m helping out with. Interested in buying Byzantine music books in North America without the retail import and shipping premiums? Talk to us. Visit http://www.byzantinemusicbooks.com, and e-mail me at richardbarrett AT johnofdamascus SPACE org.

Posts Tagged 'Greek'

Hey! Kids! Byzantine music books!

Published 10 May 2016 General , Media , music , The Orthodox Faith Leave a CommentTags: byzantine chant, Byzantine Music Books North America, byzantine notation, chant, ecclesiastical chant, Greek, hazards of church music, liturgical music, liturgy, music, random acts of chant, sacred music

Review: Cappella Romana’s Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom

Published 17 December 2013 General , Media , music , The Orthodox Faith 4 CommentsTags: alexander lingas, american orthodoxy, byzantine chant, cappella romana, chant, ecclesiastical chant, Greek, hazards of church music, liturgical music, peter michaelides, random acts of chant, rembetiko, this american church life, tikey zes

Having mused on some of the issues in the background of Cappella Romana‘s new recording, Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. Chrysostom, now allow me actually to review the disc.

Having mused on some of the issues in the background of Cappella Romana‘s new recording, Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. Chrysostom, now allow me actually to review the disc.

In 1991, Tikey Zes published a score titled The Choral Music for Mixed Voices for the Divine Liturgy that was intended to be more or less “complete” (with some abbreviations customary in West Coast parishes of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America), with all eight Resurrectional apolytikia, the Antitrisagia (“As many as have been baptized”, “Before your cross”), variants for a Divine Liturgy of St. Basil, several patronal apolytikia for parishes, as well as variants for a hierarchical service. Although up to this point Zes had relied primarily on John Sakellarides’ simplifications of Byzantine melodies as his source material, for this setting he composed his own melodies, employing a variety of polyphonic textures and different kinds of counterpoint as well. The express intent, according to the CD’s booklet, is a musical style that is less a harmonized melody and is rather polyphonic in the sense that one typically means when describing Renaissance music. The score also uses organ accompaniment, but principally to accompany unison vocal lines and only occasionally being used independently of the choir.

Cappella Romana gave Zes’ score its concert debut in 1992, prompting him to revise and expand it in 1996, with the new edition dedicated to the ensemble. It is this new edition that Cappella presents on the recording; they have supposed the second Sunday after Pentecost, when the Resurrectional cycle of modes will have reset to the First Mode — the first so-called “vanilla Sunday” since before the Lenten cycle began — and they have also included the apolytikion for St. Nicholas in the place of the parish’s patronal troparion (Zes’ home church is St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in San Jose, California). As with previous Divine Liturgy recordings, they present a good deal of the liturgical context, with the celebrant’s and deacon’s parts here presented by, respectively, Fr. John Bakas of St. Sophia Cathedral in Los Angeles (and who, coincidentally, is discussed at some length in this post from last week) and Fr. John Kariotakis of St. John the Baptist Church in Anaheim, California; in addition, parishioners of Holy Trinity Cathedral in Portland, Oregon are featured reciting the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. Some things are abbreviated; unlike The Divine Liturgy in English, the 2008 Byzantine chant release, there is not the luxury of a double-disc treatment. Nonetheless, the presentation goes to some pains to be something other than another recording of disconnected, individual pieces of music; rather, this is a Divine Liturgy that happens to be using Zes’ score.

Let’s be clear: the music isn’t “Byzantine music”, and both Zes and the choir are well aware of this (despite a comment in the booklet that is easily misunderstood, and I’ll come back to that). My previous post covered just what the implications are of that, and I suggested that Greek American polyphonic choral music might better be understood as cousin of rebetiko — that is, a folk repertoire that comes into its own in a context of emigration. That’s one aspect, perhaps, of what Zes is doing, although he is elevating it considerably; this is maybe the equivalent of somebody writing a bouzouki concerto. He is taking the music he knows from the context of the Greek American choir loft — Desby and Sakellarides and so on — and re-articulating the ethos in the musical language of an artistic high point in Western sacred music. It’s as though the Byzantines who fled to Venice eventually managed to capture the attention of Monteverdi and convince him to convert and compose for the Orthodox Church — which, again, fits pretty well with the idea of a repertoire of émigrés (although I may be stretching the notion beyond its utility).

That isn’t to say that there’s something self-conscious about how Zes uses polyphony. I don’t get the impression that he’s saying, “Hey, let’s imagine what would happen if Italian Renaissance composers wrote music for the Divine Liturgy.” I rather get the idea of a very gifted and highly-skilled composer asking, no more and no less, “What’s going to be the best that I’m able to do for the service of the Church, and what’s going to be the most fitting musical vocabulary that I know how to use for such a project?” (I refer you back to my previous post for the arguments over whether or not that’s an appropriate question to ask in the first place; I’m reviewing the recording on its own terms.) The result does not sound like Tikey Zes “doing” Palestrina or Monteverdi; at least as sung by Cappella Romana, it just sounds like beautiful church music.

Now, to be honest, I have absolutely no idea if any churches use this particular score liturgically. Obviously lots of GOA parishes use Zes’ music (for that matter, so do Antiochian parishes), but I don’t know how commonly used this particular setting is. The disc suggests that the choir that could sing it properly would certainly be a luxury ensemble; while the responses and shorter hymns are kept simple, the liturgical high points are when Zes does not shy away from gilding the things he loves. I’m trying to imagine the parish choir that could sing the longer hymns like the Trisagion or the Cherubikon, both absolutely glorious pieces of choral writing, without it being an overreach. Which brings me to the one thing I’ll say in terms of the whole organ/choir question in this review — if I close my eyes and imagine the church in which I would hear this liturgy being sung, it’s King’s College Chapel with a dome and iconostasis. This is not necessarily a bad thing, musically — in fact, I’d go so far as to say, if you’re going to go the organ/choir route, if that’s really the aesthetic you want to embrace, then you need to do it at least as well as it’s done on this recording. Yes, my consultant was quite right, Cappella Romana does sing Zes’ music like it’s Palestrina — but that also sounds like that’s exactly how it’s written to be sung. If that means the sound is like Anglican choirs singing in Greek instead of Latin or Elizabethan English — well, fine, then, so be it. Run with it. But do it well. Because if you can’t sing it at least this well, then there’s no point in using it. If you’re going to use luxury repertoire like this in your parish choir, then your parish choir better be able to fight its weight. Otherwise it isn’t going to be pleasant experience for anybody, and it will be a distraction in church, drawing attention to itself by virtue of being badly done.

Now, maybe, this score could be said to be like the Rachmaninoff All-night Vigil, which was written as a concert piece but occasionally gets broken out for liturgical use for special occasions. I will say that the Fathers John, as the celebrant and deacon, are both exceptional singers, and the net effect of the two of them plus Cappella Romana is not unlike a Bach Passion, with the celebrant and deacon perhaps in the Evangelist role. That is, there is a sense of the Divine Liturgy-as-drama with what the two clergy bring to their “roles”, so to speak, with the choral ensemble commenting on the liturgical action. Lord knows there has been sufficient analysis of the Great Entrance alone as a “dramatic” moment that maybe that’s not altogether uncalled-for; what I would say is, if you’re going to go for that, make sure you have forces at the altar and in the choir loft that can actually do it.

I said earlier that this isn’t “Byzantine music”; the booklet might seem to suggest otherwise, with the very last sentence of Alexander Lingas’ essay apparently referring to the score as “thoroughly Byzantine”. However, Lingas is not here referring to musical style or compositional technique. He is by no means offering a psaltic apologia for Zes, arguing that the music is, in fact, actually in continuity with Byzantine chant if we would just listen to it the right way. He can be doing no such thing, since this very last section of the essay is his analysis of how thoroughly un-Byzantine the music is, with its imitative and invertible counterpoint, for example. The observation that Lingas is making is that, in spite of musical discontinuity with the received tradition that we have that is in continuity with Byzantine music, it is clear that Zes is re-articulating the ethos of the Byzantine aesthetic in a Western musical language. Zes, in other words, while he is using a different musical language than Byzantine music, is nonetheless bringing considerable technical skill to bear, using counterpoint and polyphony and organ to ornament and to expand and to demonstrate virtuosity where Byzantine music ornaments and expands and demonstrates virtuosity.

(Something that I think would be very informative would be a composers’ master class, where somebody like Ioannis Arvanitis and somebody like Tikey Zes could do a detailed analysis of their own settings of the same texts with the other person, to demonstrate explicitly for an audience as well as for each other just where the points of continuity are as well as the points of divergence. Perhaps there will be an opportunity to do something like that here.)

To make a brief point relating this disc to my previous two posts — I got the following comment in a note from a friend of mine about the Zes recording: “[…]it might actually be the most ‘American’ setting…with influences from various cultures (eastern and Western Europe like our own culture here), organ etc. the irony of course is that it’s not even in English.” Looked at from a standpoint of what we might call “acculturation” or cultural adaptation, then, yes, I’d agree — and even the retention of Greek is, in its own way, a very American thing to do, since we like to emphasize and privilege our “pre-American” heritage, even in — perhaps especially in — an American context. At the same time, going by Fr. Oliver’s analysis, then the impulse to “restore” Byzantine chant is also a very “American” thing to do, given our “restorationist” tendencies.

It is telling to me that Cappella Romana has dedicated a total of four discs over the last five years to recordings that present more-or-less complete settings of the Divine Liturgy — the 2-disc set The Divine Liturgy in English for Byzantine chant, and then the Michaelides and Zes recordings. All three of these releases strike me as “pastoral projects”, as attempts to change the game in terms of the ideal of sound that’s thought of as possible — Byzantine chant in English? Yes, it can be done perfectly well in English in a way that’s still perfectly acceptable Byzantine chant, and here’s how good it can sound, too. Greek American polyphony? Yes, actually, here’s some music in that genre you’re probably not doing that you should at least think about (the Michaelides), and here’s how the really good stuff by the composer you all say you like could sound.

All of this is to say, Zes’ score is a remarkable piece of sacred choral composition on its own terms, and Cappella Romana is up to its usual high standards in terms of presentation of it. I don’t mean “presentation” to only mean singing; it’s an extraordinarily well-sung recording by all involved. Rather, the care to use the recording as the opportunity to make the case for what its liturgical use could sound like (I hesitate to use the word “should”) is also remarkable, and a hallmark of the recording. Another hallmark of the release is an exceptionally informative booklet that provides the Greek and English text of the Divine Liturgy, as well as Lingas’ essay positioning Zes’ music in the context of Byzantine music, Orthodox music more generally, and Greek emigration to the United States. Again, I will leave the argument over whether or not it “should” be used liturgically, or even recorded by an ensemble by Cappella Romana for that matter, to others in other settings; I find it to be a worthy recording of some exceptionally beautiful music composed by a man who sincerely wants to give the best of what he has, and judge it on those terms.

A word about Cappella Romana’s Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom before I review it

Published 14 December 2013 General , Media , music , The Orthodox Faith 12 CommentsTags: alexander lingas, american orthodoxy, basil crow, byzantine chant, cappella romana, chant, ecclesiastical chant, fr. ivan moody, grammenos karanos, Greek, hazards of church music, holy cross greek orthodox theological seminary, ioannis arvanitis, john michael boyer, liturgical music, medieval byzantine chant, papa ephraim, peter michaelides, random acts of chant, rembetiko, st. anthony's monastery, this american church life, tikey zes

“Although there now exist polyphonic choral settings of the Divine Liturgy by composers representing nearly the full cultural spectrum of Eastern Orthodoxy,” writes Cappella Romana‘s Artistic Director Alexander Lingas in the liner notes of their new recording, Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. Chrysostom,

“Although there now exist polyphonic choral settings of the Divine Liturgy by composers representing nearly the full cultural spectrum of Eastern Orthodoxy,” writes Cappella Romana‘s Artistic Director Alexander Lingas in the liner notes of their new recording, Tikey Zes: The Divine Liturgy of St. Chrysostom,

those produced by Greek American composers remain little known. Indeed, Orthodox Christians from Europe or the Middle East visiting Greek Orthodox churches of the United States are frequently surprised or even scandalized to hear the Sunday Divine Liturgy sung not by cantors employing Byzantine chant, but by a mixed choir singing harmonized or polyphonic music that is often accompanied by an organ. Viewed from such an outside perspective, Greek American liturgical choral music would seem to be little more than a peculiar — or, as some critics of polyphony would maintain, an ill-judged and extreme — instance of inculturation. While there can be little doubt that ideologies promoting cultural adaptation (or even assimilation) to prevailing cultural norms have influenced the development of liturgical singing in Greek America, emphasis on these aspects of its history can all to easily lead to facile dismissals that ignore its many complexities of provenance and expression.

Wow, that’s a mouthful for a CD booklet, isn’t it? And yet, there it is. As one tasked with reviewing this particular disc, I feel that I must unpack this a bit to give the recording proper context for people who may not be familiar with the issues to which Lingas refers. This is going to be rather subjective and impressionistic, but I think it all has to be said before I can write my review.

Who gets the final say of what constitutes what something “should” sound like? What is “authenticity”? What’s “authentically” American? What’s “authentically” Orthodox? What’s “authentically” “authentic tradition” or, more specifically, “authentic sacred music”? Can something be “authentic” to the “lived experience” of some Orthodox but not others? How do you work out the question of the authority to resolve such questions? We can appeal to Tradition — but interpreted by whom? Is it up to bishops? Bishops can be wrong. Is it up to musicians? Musicians can be wrong. Is it up to “the people”, whatever we mean by that? “The people” can be wrong. How do you deal with change within a rubric of Tradition so that you are neither unnecessarily reactionary nor unnecessarily innovative?

These questions are vexing for Orthodox Christians in this country. I didn’t really understand just how vexing when I first started attending services; I had initially thought that Orthodox musical issues were largely free of strife. (Stop laughing. Seriously.) I came from a high church, or at least sacramental and liturgical, Protestant setting where the jockeying was over pride of place in the schedule between the spoken service, the “contemporary” service, and the organ-and-choir service. The church where I was going had had the music-free service at 8:30am, the praise band service at 10am, and then the organ-and-choir service at 11:15, and the demographics basically amounted to the blue-hairs (and the Barretts) going to the 11:15 service and all the young/youngish middle/upper-class families going to the 10am service. (All of the really old people went to the quiet service.) The priest really favored the 10am service, and the musicians who played for that service were the ones who had his ear; the organist and the choir were rather treated as a necessary evil at best by most of the 10am crowd (I remember that the guy who led the praise band wouldn’t even say “hi” to people in the choir if our paths were to cross), and in all fairness, the organist tended to act like the praise band people were in the way. (Which, again in all fairness, from her perspective, they kind of were, with amplifiers and instruments obstructing traffic patterns for the choir if they were left out.) It really meant that there were two different church communities, and you were defined by which service you attended. (Ironically, as much as the 10am people thought the 11:15am people were snooty dinosaurs, the 11:15am service was really pretty “contemporary”-feeling in retrospect, or at least pretty low-church. As somebody who had been confirmed in more of a high-church context, my Anglo-Catholic instincts tended to be smiled at but ignored.)

In 2004, my second year in the School of Music at IU, I was asked to write a set of program notes for a choral performance I was singing in of Gretchianinoff’s setting of the All-Night Vigil, outlining the liturgical context of the service. I did the best I could with what I thought I knew at the time, and I included the following discussion of the a cappella tradition within Orthodoxy:

Historically, instruments have no place in Orthodox worship; organs are a recent development in some Greek parish churches in the United States, but those are generally examples of communities that have moved into pre-existing buildings that already had organs, and then simply adapted to what was there.

My first glimpse into just what disagreements there could be over Orthodox church music was when Vicki Pappas, the then-National Chair of the National Forum of Greek Orthodox Church Musicians, came to the Gretchianinoff concert. She talked to me about the notes afterward and said, “Very good on the whole, Richard, but that’s just not true about organs. Greeks love their organs, and have built many churches with the intent of having them.” That seemed quite contrary to what I had been told up to that point about a cappella singing being normative, and I wasn’t clear on where the disconnect was. Little did I know.

Last year, the Saint John of Damascus Society was asked to write a script for an hourlong special on Orthodox Christmas music that would have been aired on NPR. I wrote the script, but for various reasons the full program shrunk down to a segment on Harmonia instead. Anyway, as I was writing the segment and assembling the program for it, one of the people I was consulting with objected to Cappella Romana‘s recordings being used for some of the contemporary Greek-American polyphonic composers like Tikey Zes. “They sing Tikey’s music like it’s Palestrina,” this person told me. “Real Greek Orthodox choirs don’t sound like that. Let me get you some more representative recordings.” The problem, though, was that the recordings this person preferred weren’t really up to broadcast quality. They were more “authentic” to this person’s experience of how the music is used in church, but they were problematic to use in a setting where one needed to put the best foot forward.

Coming from an Anglican background, this struck me as an odd criticism, and it still does. My church choir in Bellevue didn’t sound anything like the Choir of King’s College at Cambridge, but I would certainly rather give somebody a King’s CD if I wanted them to get an idea of what Anglican music sounds like rather than get an ambient recording of a service of my old choir. Is it representative of what it “really” sounds like? Is it representative of what it should sound like? I can’t definitively answer either question, but it’s the ideal of sound I have in my ear for that repertoire. Whether or not the average parish choir sounds like that isn’t really the point. Still, that’s an argument that doesn’t satisfy the “lived experience” criterion.

At the same time, the presence of robed choirs and organs means that there’s some jostling that happens with people for whom the Orthodox Church’s traditional repertoire is chant, period, with opinions strongly held on both sides. There’s the issue that the Ecumenical Patriarchate issued an edict in 1846 forbidding the liturgical use of polyphonic music, and I don’t think that anybody denies that this exists, but it seems to me that there’s a good deal of disagreement about just what it means for American congregations in 2013. In any event, the fact that Orthodoxy still usually follows the one-Eucharist-per-altar-per-day canon means that you can’t split a church community along musical lines exactly, but nonetheless the solution in a lot of places is to institute aesthetic fault lines between services. Generally, what this looks like is that that Matins/Orthros is the domain of a lone cantor (or two or three) up until perhaps the Great Doxology, at which point it’s taken over by the choir. This interrupts the intrinsic unity of the services as they are intended to be served according to present-day service books, but it’s a solution. Speaking personally, I have put a good deal of time and effort over the last several years trying to become at least a competent cantor, and I’ve experienced the glory that is Orthros and Divine Liturgy being treated as a seamless garment sung in one musical idiom by the same people throughout, but I’m also not fundamentally thrown off by the presence of a polyphonic choir singing polyphonic repertoire.

While I’m thinking about it — I was surprised to discover that there is not, exactly, agreement over what exactly constitutes “Byzantine chant”. As I was taught, “Byzantine chant” indicates a particular process of composition of monophonic melodies for Orthodox liturgical text, employing a particular musical idiom with its own relationship to the text, theoretical characteristics, notational system, vocal style, and practice of ornamentation, informed by oral tradition (or, to use words perhaps more familiar to Western musicians, “performance practice”). In other words, it is not a fixed, bounded repertoire, but rather a living tradition; you can compose “Byzantine chant” for English texts by following the compositional process and sing the result with the proper style and performance practice. For English, this perspective probably prefers the work of Ioannis Arvanitis, Basil Crow, Papa Ephraim at St. Anthony’s Monastery, John Michael Boyer, and the like. This is also essentially the point of view presently taught at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology by Dr. Grammenos Karanos (more about them here).

At the same time, I’ve encountered the point of view — from both cradles and converts, people who are theoretically knowledgeable and people who aren’t — that that’s not Byzantine chant at all. Byzantine chant, according to some, actually is a fixed, bounded repertoire for Greek and Arabic; for one reason or another, so this point of view goes, a fresh setting for an English text might be a number of things, but it isn’t Byzantine chant anymore. (Either because the compositional process is imperfect for English, doesn’t work at all for English, or is irrelevant in the first place, depending on to whom one speaks.) The whole idea of formulaic composition here is set aside; it’s the melody that already exists that’s important, not the relationship of the melody to the text by way of those melodic formulae, and that melody needs to be preserved for it to still be “Byzantine chant”, even at the expense of proper formulae or orthography. This perspective would find, for example, Fr. Charles Baz’s transcriptions of the Basil Kazan Byzantine Project into Byzantine notation not just acceptable, but preferable to the work of the composers mentioned above.

And then there are still other “sides” within what I’ve outlined above. The bottom line is, there is more than plenty to argue about where music is concerned. For my own part, I try to be a specialist but not a partisan, and I think context matters. I don’t think that means “anything goes”, but to the extent that traditions of liturgical crafts have historical contexts (even Byzantine chant!), I’m not sure how much it accomplishes to pick fights. Part of the problem, as I’ve experienced myself, is that there aren’t a lot of people who are sufficiently well-trained Western musicians and Byzantine cantors, such that they can adequately participate in, or even comprehend or relate to, both contexts. There are some, but not many, and there’s generally not a lot of interest on the part of one “side” in learning about how the other “side” does things. I am able to go back and forth between the psalterion and the choir loft to some extent — I suppose I’d say I’m equally clumsy in both contexts — and I’m interested in what goes on in both, but I have my own opinions that I bring with me, certainly. (You don’t say, you’re both thinking.) I don’t like the hodgepodge of whatever random music might be thrown together that it seems to me that the choir loft can become. I don’t like a structure of liturgical responsibility that effectively tells a cantor, “We want you to cover all of the services that nobody comes to” (let’s be honest here). At the same time, if “Byzantine chant” is understood principally as “what the old guy whose voice is nasal and can’t stabilize on a single pitch, and who should have stepped down 25 years ago but didn’t because there wasn’t anybody to take his place, does before Divine Liturgy”, then that’s its own problem, one that we cantors need to be proactive about fixing. In general, we church musicians, cantors and choristers alike, need to be a lot more proactive about, shall we say, reaching across the nave and educating ourselves about our own musical heritage and where the stuff we might individually prefer actually fits in.

Okay, so then there’s the question of how an ensemble like Cappella Romana fits into this picture. As a professional choral ensemble that specializes in a particular kind of repertoire — Orthodox liturgical music in all of its variety — but one that is also led by a Greek Orthodox Christian and that has a substantial, though not exclusive, Orthodox membership on its roster, what is their role? Do they have a responsibility to follow a particular ecclesiastical agenda, even though they’re not an ecclesiastical organization? To put it one way, is their job descriptive or prescriptive? Are they a de facto liturgical choir that is only to record and perform in concerts the music that “should” be done in churches? Or, as a performing ensemble first and foremost, are they perhaps the kind of ensemble that should be exploring repertoire like Peter Michaelides, medieval Byzantine chant, Fr. Ivan Moody, and so on? Maybe they get to be the King’s College Choir, as it were, that records and performs things that would likely never be used liturgically, nor be appropriate to be used liturgically. But then, just as the Choir of King’s still sings daily services, Cappella has its “pastoral” projects, like The Divine Liturgy in English, where they are most definitely trying to disseminate an ideal of sound for churches to emulate. Alas, in some circles this argument of a two-sphere approach generates the the rather grumpy insistence that “Orthodoxy doesn’t do art”, or at the very least that art is a luxury that Orthodoxy cannot afford in in its current context in the New World. To me, that’s absurd, but as I have my own Orthodox artistic music project in the works, perhaps I’m not the most objective of critics where that point of view is concerned. At the very least, even if one is to ultimately dismiss liturgical use of the repertoire, I might suggest that Greek-American choral repertoire, not unlike the Greek idiom of vernacular music known as rebetiko, is worth understanding on its own terms at a musical and sociological level. (If you’re wondering what I mean by that, a full discussion is perhaps beyond our present scope, but I might submit that Greek American choral music, like what I understand is the case with rebetiko, can be seen as essentially a folk repertoire born in a context of emigration.) At any rate, thank God that it’s an ensemble like Cappella Romana taking it on, where the leadership and at least some of the membership have an intimate understanding themselves of the various elements at play.

And finally to the CD itself, which, because of the reasons mentioned by Lingas in the essay and what I discuss above, is in the unenviable position of not being able simply to be a recording of sacred music, but rather a recording that must be interpreted as a statement of something by people who don’t want the music contained therein legitimized, AND by people for whom this is the right music, but the wrong way to sing it. Jeffers Engelhardt, can you help me out here?

Well, to give you a capsule review (full review will be in the next post, now that I’ve got all of this stuff off my chest), if you come to the disc without needing it to be a statement of anything in particular, you will find that it is a beautifully-sung recording of some gorgeous music. The essay in the booklet about the music’s historical context is fascinating, both for what it says as well as what it doesn’t say. And yes, Cappella sings Tikey’s music like it’s Palestrina, and you know what? It sounds glorious. So, “authentic” or not, works for me.

Be right back.

Byzantine chant at Holy Cross and CD Review — All Creation Trembled: Orthodox Hymns of the Passion Service

Published 10 December 2013 Academia , General , Media , music , The Orthodox Faith 11 CommentsTags: all creation trembled, archdiocesan school of byzantine music, byzantine chant, chant, ecclesiastical chant, grammenos karanos, Greek, hazards of church music, holy cross greek orthodox theological seminary, john michael boyer, liturgical music, liturgical texts and translation, liturgy, rassem el massih, sacred music

This has been a ridiculous semester on multiple fronts. I have been assisting with a course where there has been a constant cascade of homework to be graded pouring on top of my head, plus I’ve been trying to write a dissertation, plus I have a child I’m trying to rear, plus I’ve had extracurricular activities, plus I’ve got a 1:15 commute to church on Sunday I didn’t have a year ago, plus I have a spouse dealing with all of exactly the same things. Too much fun.

It is an exciting time for Byzantine chant in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese; the Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music just performed an invited concert at Agia Irini Church in Constantinople, Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology recently unveiled their Certificate in Byzantine Music, and they also released a new CD, All Creation Trembled: Orthodox Hymns of the Passion Service, recorded by their new full-time professor of Byzantine music Dr. Grammenos Karanos and his students.

It is an exciting time for Byzantine chant in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese; the Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music just performed an invited concert at Agia Irini Church in Constantinople, Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology recently unveiled their Certificate in Byzantine Music, and they also released a new CD, All Creation Trembled: Orthodox Hymns of the Passion Service, recorded by their new full-time professor of Byzantine music Dr. Grammenos Karanos and his students.

As somebody who has been fortunate enough on a small handful of occasions to attend services in the Holy Cross chapel, I can happily tell you that All Creation Trembled is a pretty accurate snapshot of at least the aural experience of the chapel. The students chant in antiphonal choirs, often divided by language (while not represented on this disc, Thursday evenings have of late been dubbed “Antiochian night”, where the Antiochian seminarians get the right choir and chant in Arabic, while the left choir gets Greek.) They do so from classically composed scores in Byzantine notation, in both Greek and English, and they do so under the expert direction of Dr. Karanos, who functions as the protopsaltis (first cantor) of the chapel. At the same time, they have also in the last few years had a group of particularly strong students to help, especially John Michael Boyer, who has been the lampadarios (director of the left choir) of the chapel for the last couple of years, and Rassem El Massih, a Lebanese-born seminarian who studied Byzantine chant with Fr. Nicholas Malek at the Balamand before emigrating to the United States. Other standouts, at least when I’ve been there, have included Niko Tzetzis, Gabe Cremeens, Andreas Houpos, and Peter Kostakis (and others — forgive me if I’m blanking on a couple of names).

The disc’s repertoire is hymnody from Holy Week, specifically from the Matins for Holy Friday (sung on the evening of Holy Thursday), and it is about 50/50 Greek and English. The English scores, composed by Boyer, employ the translations of Archimandrite Ephrem (Lash), occasionally modified by Boyer for metrical purposes. The recording quality is very clean, and the singing is robust and clear throughout, with an ensemble sound never dominated by one voice. This in particular is a point I want to praise; the recording could have very easily become “The Karanos/Boyer/El Massih Liturgical Variety Hour”, and it never goes there; even Karanos himself is only heard a couple of times as a soloist. A sense of the chapel choir as, above all, a liturgical ensemble is always maintained, with everything they sing and how they sing it dictated by liturgical concerns. The result is well-balanced and it sounds wonderful. If it is not quite professional-level — some background noise creeps in, and sometimes it sounds like the microphones are not quite optimally placed — well, it’s still an excellent entry in the category of American recordings of Byzantine chant, and it still captures the moment very well, a moment that represents a revitalized program in its early days, one that is starting to have an impact elsewhere — El Massih is now teaching Byzantine chant at St. Vladimir’s Seminary, for example, and that can only be for the good. If this can be taken as a statement of intent on Dr. Karanos’ part, then the future is encouraging.

The Certificate program also suggests an encouraging future; it’s intended to be the equivalent of a conservatory program in Greece, and it looks like it’s pretty comprehensive. I know one person who was going through a try-out version of it, and it sounds like it would be well worth the two years. One hopes that eventually there might be some financial assistance available for students who would want to go through such a program but aren’t there for M.Div. work. I would also very much like to see the program replicated elsewhere (I’ve discussed my own curriculum proposal elsewhere); if I have any particular critique of all of these efforts, it is that they are ultimately inaccessible for those of us not in the Northeast. I would have no problem with the Northeast functioning as a central location for a network of programs, but access to this training and to these kinds of opportunities needs to be geographically more spread out than it is. In the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese alone, there’s no reason there couldn’t be a formal training program and Byzantine choir in every Metropolis (although color me skeptical about attempts to do this kind of thing online as a normative approach — I can’t imagine any of my voice lessons from the old days going well if done that way).

I leave you with the video of the Archdiocesan School’s concert at Agia Irini. Enjoy.

Newly posted: Hansen and Quinn, notes and answers, Unit VIII

Published 1 May 2013 Academia , General 1 CommentTags: Greek, hansen & quinn, my kids ARE learning latin and greek as newborns

As I promised when I posted the notes for Unit VI, for every $150 tipped, I promise to get the next unit posted within a week. I have to be honest, between Orthodox Holy Week and the end of the semester, I’m a day late (the $150 threshold was met a week ago yesterday), but hopefully I may be forgiven this time. In any event, here you go – I have posted the notes for Unit VIII. Many thanks to all of you who have taken the time to tip.

If you’re looking at this before 16 May 2013, perhaps also consider pledging to this other project I’m working on; if you do that, I’m happy to count that towards the $150 threshold. Just let me know via a comment that that’s what you’re doing, and once the pledge is recorded I’ll update the total here.

As always, if you’ve got corrections, questions, or comments otherwise, let me know — enjoy!

Just posted: Hansen and Quinn, notes and answers, Unit VII

Published 15 March 2013 Academia 1 CommentTags: Greek, hansen & quinn, my kids ARE learning latin and greek as newborns

As I promised when I posted the notes for Unit VI, for every $150 tipped, I promise to get the next unit posted within a week. Well, it’s taken two years and nine months to break that threshold, but it was indeed broken on Monday, so here you go – I have posted the notes for Unit VII. Many thanks to all of you who have taken the time to tip.

As always, if you’ve got corrections, questions, or comments otherwise, let me know — enjoy!

This is what happens when you tell me I can’t do it

Published 19 January 2013 Academia , Beginnings 7 CommentsTags: Greek, Latin, my kids ARE learning latin and greek as newborns, ways of making lemonade from academic lemons

Seven years ago today, somebody who was very well-informed about how such things worked told me that it was highly unlikely that I could ever be competitive for IU’s History graduate program, given an undergraduate degree in music performance rather than in something properly considered part of the Humanities, and particularly given no real background in Latin or Greek.

I’m pleased to note that as of this week, I have passed my doctoral-level Greek and Latin exams. The Greek exam requirement was satisfied last summer (thank you, Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Greek Summer School), and I took my Latin exam this last Tuesday, which consisted of passages from St. Jerome’s Life of St. Hilarion, The Acts of the Divine Augustus, and Agnellus’ Book of the Pontiffs of Ravenna. My examiners seemed very pleased.

Now, on to my oral exams, which are scheduled for 29 March. Because I never do anything in the right order, I more or less have a dissertation proposal once my orals are out of the way, so God willing, I’ll have advanced to candidacy by the end of the semester.

I may still yet have a real job before I’m 40. We’ll see.

CD review: GOA Archdiocesan Byzantine Choir, Μέγαν εὕρατο (Vespers for St. Demetrios)

Published 17 July 2012 General , music , The Orthodox Faith 3 CommentsTags: archdiocesan school of byzantine music, byzantine chant, chant, ecclesiastical chant, Greek, hazards of church music, liturgical music, random acts of chant, sacred music

Archdeacon Panteleimon Papadopoulos was kind enough to send me a review copy of Μέγαν εὕρατο, the new recording released by GOA’s Archdiocesan Byzantine Choir.

Archdeacon Panteleimon Papadopoulos was kind enough to send me a review copy of Μέγαν εὕρατο, the new recording released by GOA’s Archdiocesan Byzantine Choir.

The disc is a collection of the festal hymnody sung at Great Vespers for St. Demetrios (chosen to honor Abp. Demetrios), including the Anoixantaria (for those unfamiliar with the practice, Psalm 103 from “Thou openest thine hand, they are filled with good…” to the end is theoretically sung rather than merely read for major feasts in present-day Byzantine practice, although in my experience this is one of those things that a lot of people don’t do with the excuse that “nobody does that”), “O Lord I have cried” with stichera, Doxastikon, and Theotokion, hymns for Litya and Artoklasia, aposticha, apolytikion, and “Many years” for Abp. Demetrios. The ensemble, if I understand correctly from the list of participants, is a group of psaltes largely from the Northeast, including Dr. Grammenos Karanos, the current professor of Byzantine music at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, and others from the New York area.

The first thing that must be said is that this is a wonderfully sung program; the wall of sound produced by these gentlemen is never less than first rate, and hymns with slower, more melismatic textures such as the Anoixantaria are particularly beautiful.

One of the things that I try very much to do is to view recordings like this, labors of love by people who are clearly far more knowledgeable and able than I am, as master classes, opportunities to learn finer points that I haven’t had the opportunity to learn otherwise. I have been informed by a particular point of view that makes certain assumptions, and not everybody is necessarily informed by the same perspective and assumptions. (For example, given a number of factors, I tend to assume that even for Byzantine chant, choirs are ideal, with solo cantors needing to be judiciously used. However, I am well aware that for many people, for this repertoire, the solo cantor tends to be the assumption in terms of performing forces, with choirs only happening for special occasions.) To that end, there are questions that I have about aspects of the recording. Some of these questions veer into critical territory from an entirely subjective musical standpoint, but may well be entirely answerable in terms of style.

First off, something that is immediately apparent has to do with repertoire choices. These are, with a couple of exceptions, not selections out of what have been represented to me as “the classical books”. The melody used for the prosomoia at “O Lord I have cried”, for example, “Ὢ τοῦ παραδόξου θαύματος”, is not the melody found in the Irmologion of Ioannis Protopsaltis, and the Kekragarion is not from the Anastasimatarion of Petros Peloponessos, either. They’re not bad, necessarily (although I have to say I definitely prefer Ioannis’ melody for the prosomoia), but I am curious about what informed the selections.

Second, there’s a tendency throughout the disc to cut off of endings of phrases (including isokratema) quite sharply; this is something that makes sense to me to do as a solo cantor, so that the congregation knows that the places where you’re breathing are intentional, but it makes less sense in a choral setting unless there’s a specific stylistic reason to do so. It’s obviously a choice, and one that is executed distinctively, carefully, and consistently, but I’m left wondering if it’s necessary for it to be as prevalent as it is here.

Third, the apichimata are sung chorally, which makes me wonder if there’s a performance tradition for apichimata that divorces them from their function. Soloists sing the verses at the “O Lord I have cried” stichera, so it’s not simply a matter of everything being choral for purposes of this disc.

Fourth, as performed, the ison moves around a lot more than I’m used to. I’m aware that this is a point where it seems everybody and their dog will tell you “the real way” you’re supposed to realize the drone, so I assume this is a stylistic point as well.

Strictly in terms of the physical presentation of the disc, it would be nice to have had more of a booklet; the performance is entirely in Greek, and while many of the texts are reasonably familiar, for those not used to Greek an included translation would help make the product more accessible. Doubtless this is a function of production cost; perhaps an “online booklet” or some such would be a way of accomplishing this in a cost-effective manner next time.

To sum up: this is a gorgeous-sounding recording that is probably best described as a snapshot of the state of Byzantine chant in Greek in the Northeast, which seems to be healthy indeed. I’ll be very interested to hear what the Archdiocesan Choir does next — the Archdiocesan School seems to doing a lot to try to raise the profile of Byzantine chant, and I’m looking forward to future developments.

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese releases standard version of Paschal apolytikion

Published 6 April 2012 General , music , The Orthodox Faith 8 CommentsTags: american orthodox music, american orthodoxy, byzantine chant, byzantine notation, chant, christ is risen, ecclesiastical chant, Greek, greek orthodox archdiocese of america, hazards of church music, χριστὸς ἀνέστη, let's make English an inflected language again, liturgical music, militant americanist orthodoxy, music, my kids will learn latin and greek when they're newborns, national forum of greek orthodox church musicians, Pascha, paschal apolytikion, random acts of chant, sacred music, st john of damascus society, this american church life, vicki pappas, we need more american saints

About a year ago, Vicki Pappas, national chair of the National Forum of Greek Orthodox Church Musicians, circulated an e-mail asking for people to send her the English translations of the apolytikion for Pascha (Χριστὸς ἀνέστη/”Christ is risen”) that were used in their parishes. This would be in aid of a standard English text for the entire Greek Orthodox Archdiocese. Despite not being at a GOA parish, I sent her the translation we use at All Saints.

Somewhere around late fall or early winter, following a St. John of Damascus Society board meeting, she asked if I would be willing to round up a few of my choir members to record the version that they were trying to settle on as the final draft. The recording would serve as a model, principally for priests. After Christmas, I put together a quartet, we learned it and recorded it, Vicki liked it, and said that the Synod still had to decide if it was the final version or not.

Earlier this week, the standard English version of the hymn for GOA was released. You can find it here. Alas, that’s not us singing on the model recording — it would appear that it went through at least one more round of revision, because that’s a different text than what we had, but oh well.

I am appreciative that a Synod would take the time to try to get everybody on the same page with respect to a particular hymn text, and I suppose this is as good as any to start with. I am also appreciative that GOA would go to the trouble of making sure that it is available in both staff notation as well as neumatic notation. There has been some discussion in some circles about how closely it follows proper compositional conventions; I would never dare to argue proper application of formulae with some of the people talking about this, but my guess is that the main point raised was probably known, and that preference was given to where people would be likely to breathe. It’s an issue that I suggest stems from the translation more than anything, and from what Vicki has told me, every nuance of the translation was discussed thoroughly, so what I think I know at least is that it’s a version of the text that says exactly what the Synod wants it to say. I’ll acknowledge that I don’t find this text to be note-perfect compared to how I might translate the Greek; to begin with, in modern English, “is risen”, while it used to be how you do a perfect tense in English, doesn’t really convey the same sense of the action as preterite ἀνέστη or even qam for the Arabic speakers — “Christ rose” would be the literal sense, but that doesn’t really “sing” the same way. “Christ has/hath risen” is an acceptable compromise, since the distinction between simple past and perfect is muddier in English than it is in Greek. And “trampled down upon” seems to me to be a little bit overthought as a way of rendering πατήσας. Still, I’d much rather sing this version than the one that’s normative for my parish, where the Greek melody is left as is, requiring “Christ is risen from the dead” to be repeated, usually with a rhetorical, campfire-style “Oh!” thrown in beforehand — “Christ is risen from the dead, oh! Christ is risen from the dead!” etc. Ack.

In any event, between being willing to argue about a standard text and acknowledging the neumatic notational tradition, there is much I wish the Antiochian Archdiocese would emulate here, and I congratulate GOA on taking the time and energy to at least make the effort, even if there wind up being tweaks down the road. I’m a little disheartened by the response I’ve observed in certain fora that basically criticizes GOA for making their standard version a brand new variant that nobody outside of GOA will ever use, that that’s hardly a unifying move across jurisdictions, not when there are translations that are common to both the OCA and AOANA. Well, maybe, but kudos for GOA for at least trying to get their own house in order first, even if maybe it winds up being a beta test.

Review: Cappella Romana, Mt. Sinai: Frontier of Byzantium

Published 4 February 2012 General , Media , music , The Orthodox Faith 8 CommentsTags: alexander lingas, american orthodox music, byzantine ars nova, byzantine chant, cappella romana, chant, ecclesiastical chant, Greek, hazards of church music, john michael boyer, liturgical adventures, liturgical music, liturgy, lycourgos angelopoulos, medieval byzantine chant, mt sinai frontier of byzantium, my kids will learn latin and greek when they're newborns, random acts of chant, sacred music, st catherine's monastery sinai, the service of the three youths in the fiery furnace, the three youths in the fiery furnace

Cappella Romana is an ensemble that’s hard to pin down. Are they an early music ensemble? Yes, sort of, but they don’t generally do Bach or Monteverdi. Are they a sacred music ensemble? Yes, but they’re not affiliated with a specific church institution (i. e., a cathedral or parish). Are they a world music ensemble? Sort of, since much of the music they sing originates in the Mediterranean, but not exactly. Are they a contemporary music ensemble? Yes, sort of, but much of the contemporary music they do is decidedly in an older tradition. Are they a pastoral, confessional affair? Of sorts, I suppose, although their membership is by no means entirely composed of Orthodox Christians. Are they a scholarly project? Well, yes, they’re kind of that too, given that the booklets tend to be article-length affairs with footnotes and bibliography. I suppose you could say that they’re an early world contemporary sacred music vocal ensemble that’s run by a musicologist.

They’ve been extraordinarily productive in terms of recorded output in the last eight years; since 2004 they’ve put out some eight discs (ten if you include the compilation for the Royal Academy’s Byzantium exhibit and their contribution to the Choral Settings of Kassiani project) that have run the gamut — medieval Byzantine chant, Russian-American liturgical settings, a long-form concert work by an American master, Western polyphony, Greek-American polyphonic liturgical music, and Christmas carols (of a sort). Their recordings also continue to get better and better; I picked up their discography in 2004 starting with the Music of Byzantium compilation of various live and recorded excerpts, followed by Lay Aside All Earthly Cares, their collection of Fr. Sergei Glagolev’s music, and then 2006’s The Fall of Constantinople, a program I had heard them perform here in Bloomington. Comparing just those three discs to each other, there’s a noticeable jump in quality, and then comparing them to recent releases such as the Peter Michaelides Divine Liturgy, it’s clear that they’ve found a groove in the studio (as well as perhaps in the editing booth) and they’re riding it now. They’re recording music nobody else is really doing, and while that means it’s hard to know what an applicable comparandum for any particular recording might be, it’s clear listening to it that they’re doing it at a very high level regardless, and the good news about the lack of comparable recordings is that it reveals the sheer richness of the Orthodox musical heritage. Arvo Pärt and Rachmaninoff are great, but there’s much, much more that you can do.

Mt. Sinai: The Frontier of Byzantium fits into this scheme by presenting music from late medieval Byzantine chant manuscripts from St. Catherine Monastery at Mt. Sinai, one of the key crossroads for Eastern Christianity. A Chalcedonian monastic outpost dating as far back as the days of Justinian in the middle of non-Chalcedonian Egypt, it is a treasure house of some of our earliest witnesses to the Christian iconographic tradition (since it was a place of refuge from the iconclasts), and its library of manuscripts in virtually every language of the Roman oikoumene is a witness to the catholicity of the Empire that produced them. The musical selections include portions of a Vespers for the monastery’s patronal feast, as well as the Service of the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, a quasi-liturgical drama that would have been served between Matins and Divine Liturgy on the Sunday before Christmas.

The Vespers material is interesting, particularly how Psalm 103 is treated. It is something of a mix of reconstructed Palestinian practice and present-day Greek tradition, where the first three verses are sung antiphonally, and then Koukouzelis et al.‘s setting of the Anoixantaria (the section of Ps. 103 that starts with, “Thou openest thine hand, they are filled with good…”) is interpolated with Triadika, short refrains glorifying the Trinity. It’s an approach to psalmody (in the literal sense of the word) that is generally eschewed in modern American parish practice; we tend to treat whole psalms as something to get through as quickly and as plainly as possible. Of course, just singing the Anoixantaria can take as long as 20 minutes depending on whose setting one is doing, so when parishes want to get Vespers done in half an hour or less, that’s the way it is. Elements like this emphasize how, ideally, our worship needs to be unhurried; we’re on God’s time, he’s not on our time.

The Service of the Furnace portion is lovely. It’s a real curiosity, liturgically speaking; the notes refer to it having been part of the practice of Constantinople and Thessaloniki (and subsequently Crete), and something that developed during the so-called “Byzantine ars nova“, where an artistic and spiritual flourishing was paradoxically occurring in the East at the same time as the political collapse. I’m left wanting to know more about how exactly how it developed, and why, and why it didn’t catch on elsewhere in the Orthodox world.

There are several musical textures in the Furnace section, solo to choral, syllabic to highly melismatic, and they’re all handled with beautiful musicianship and and some of the best male ensemble singing you’re ever likely to hear on a CD. One thing I’d point out is that this actually is something that has been commercially recorded before and is more or less available, even if you have to know where to look for it. Lycourgos Angelopoulos and the Greek Byzantine Choir (EBX) recorded parts of it for a Polish release called “Byzantine Hymns”, and while I have yet to actually find this for purchase anywhere, you can find their rendering of the Service of the Furnace hymnody on YouTube. Obviously there’s a bit of a difference in approach; EBX tends to have a different vocal quality all around that I would describe as a little more suntanned and weatherbeaten, and they’re singing the material the way they sing at church every Sunday. EBX also employs a children’s choir for the Three Youths themselves, which is apparently the historical practice and sounds fantastic, but I can see several reasons why that might be an undesirable layer of complexity for Cappella’s presentation.

One other thought — something that a recording like this might help to give a glimpse of is the vitality of the Christian tradition in the Middle East. St. Catherine’s Monastery is an Egyptian witness to a faithful, diverse, cosmopolitan Christianity in the Roman world, and that Christianity is still there, alive, and hanging on. Projects like this show that it is a witness that has much still to teach us.