A comment prompted me to look up a series of e-mail I sent to the members of my choir from the thus far one-and-only PSALM national conference held back in August of 2006. This was back in the days before I had a blog. I sent these to my choir partially because I wanted them to engage some of the things I was hearing while I was there; truth be told, I’m not sure they all understood why they were getting long e-mails from me. Such is life.

Reading through them, it seemed perhaps worthwhile to share some of those notes here. My perception — and someone can correct me if I’m wrong — is that PSALM peaked with this event; I think there was talk back then about trying to set up regional PSALM identities and events and then do a regular national conference every other year, but none of that ever happened, for better or for worse. My experience with the PSALM Yahoo! group in its present form is that the ideals expressed five and a half years ago are by no means universally held these days, or even necessarily approved of. I can’t really say for sure I understand what’s going on there, but there we go.

Anyway, without further ado —

—

Day 1: Hello from Chicago! Day 1 has been packed with a lot of stuff that hopefully will be useful for all of us in the long run, and the days to come look similarly stuffed. The Indiana representation has been significant: the opening remarks were from Fr. Sergei Glagolev, an Indiana native; Vicki Pappas and Fr. Joseph Morris (from Ss. Constantine & Elena in Indy) were both part of a panel discussion; the Paraklesis service was sung by IU alum Jessica Suchy-Pilalis; and I finally had the occasion to meet Lori Branch, about whom I have heard so much over the years. She sends along her love and best wishes to all who might remember her.

We had a rehearsal for the Divine Liturgy Saturday morning, and about two-thirds of the conference participants are making up the choir–that is, probably somewhere around 100 people. It’s like the Sunday of Orthodoxy choir, only about four times the size. In the enormous nave that St. George in Cicero has, one is bathing in the sound when all of sing. It’s quite something. Mark Bailey, one of the instructors in liturgical music at St. Vladimir’s, is conducting the conference choir–and it might be worth mentioning that, when we looked at the “Lord, have mercy” sections, the first thing he did was tell us to drop the r in the word “Lord” so that it came out “Lohd”. Just so you know that it’s not that I’m crazy. (Well, not just that I’m crazy, anyway.)

The Paraklesis service was lovely–unison women’s chant from Dr. Suchy-Pilalis and one other. Really very beautiful.

I’ll have a full account of all the goings-on later, but there are a number of things panelists and clergy said which I’m chewing on already. Some of them are pretty challenging and clear-cut in terms of communicating a strong point of view and expectation:

“There is no such thing as a quick fix, only hard work… We have to have the ability to change, because when things don’t change, they’re dead.”–Fr. Sergei Glagolev. Fr. Sergei also challenged us to think about what we want to pass on to the next generation in terms of singing in church.

Fr. Joseph stressed the need for the choir to be dignified and sober, and to have a servant mentality–that we come on time, and we are prepared. “If you can’t make it on time, you can’t make it on time,” he said. “Better to sing with the faithful in that case. You’re not a bishop.” He also noted that, in his parish, there is the expectation that the singers treat Vespers, Matins, and Divine Liturgy as one piece–that is, if someone is singing in the choir for Divine Liturgy, he expects them to have been there for Vespers and Matins as well. “My expectation is that my singers are Orthodox in practice as well as name,” he said.

Valerie Yova, PSALM president, observed that, in general, there is a lack of effective musical leadership in the Church in this country, and noted the following symptoms/factors:

- Choirs are shrinking and aging

- People are living further and further away from where they go to church

- School music programs are dying

- Parishes are falling into financial trouble

- There are an almost impossibly small number of places to be trained as an Orthodox church musician

- The old chanting masters are dying and not being replaced

- The musical element of worship is being devalued

The panel discussion (David Drillock, Fr. Joseph, Fr. John Rallis, Fr. Lawrence Margitich, Fr. John Finley, Alice Hughes, Carol Wetmore, Rachel Troy, and Vicki) observed that synergy between choir director, singers, and clergy requires time and regular effort, and e-mail cannot be all there is. To that end, not only are regular rehearsals vital, but clerical involvement in rehearsals on some regular basis is also important. Vicki Pappas made the point that volunteerism cannot be an obstacle to excellence, that church musicians have a sacred role, that of being responsible for leading the people’s worship, and that this should inspire us to better things. Fr. Joseph followed this up by saying, cf. St. John Climacus, “If it is possible for one, it is possible for all.” One priest (Fr. Lawrence Margitich, I think) put it this way: we shouldn’t confuse volunteerism with stewardship. As church singers, we are stewards of God’s talents, not mere volunteers, and we should act and think of ourselves accordingly. David Drillock, choirmaster emeritus at St. Vladimir’s expressed this by saying that being in the choir should be a “high calling”.

Other nuggets from the panel: if we as singers are truly connected to the text we’re singing, it will be communicated to the congregation naturally. Also that the church school should be excellent recruiting ground for the choir. Fr. Joseph also suggested that congregational singing should not drag the Liturgy down; it should appropriately done and led. Dovetailing onto that, Vicki suggested a clear intent with respect to which sections we should encourage the congregation to sing, and those which we intend the choir to sing. Having said that, the panel followed that up by saying that it is foolish to replace something people love unless one knows it’s being replaced with something they’ll love at least as much.

Fr. Thomas Hopko, Dean Emeritus of St. Vladimir’s, minced no words: “I disagree that dead things don’t change. Rather, dead things become more rotten, corrupted and stinky.” He also issued a rather direct challenge: “The Orthodox Church seems to be the only place on earth where you don’t have to be competent to be asked to do something. How does this come about? What happened? Why will people join a community choir, not miss a rehearsal, pay attention to the choir director, and then then not do the same in their parish choir? If we’re not taking church and everything we do in it seriously, then we’re just re-arranging deck chairs on the Titanic. You can’t raise the bar when you still have to convince people that there’s a bar to be raised in the first place.”

In aid of this sentiment, he told the following story: a parish started talking about buying a new chandelier. It came to the parish council, and one person stood up and said, “I am absolutely against this. We don’t need a chandelier, we don’t want a chandelier, and we can’t pay for a chandelier.” The priest asked, well, what do you mean? “It’s too expensive,” the man said, “and we don’t even know where to buy one.” (Scattered laughter from the audience.) He went on: “Plus, there’s nobody in the parish who can play one, and it’s not even part of our tradition anyway.” (More laughter from the audience.) He finished by saying, “I just can’t understand why we’re talking about buying a chandelier when what we really need is more light!” (Peals of laughter from the audience.)

Like I said, all very challenging stuff, but there was a truly remarkable consistency to the message I heard today. It’s going to take me a while to process all of it, but there was one more thing that was stressed today, and I’ll close with that for now–

Fr. Thomas Hopko also said that, as church musicians, in terms of purpose and practice, we must start no other place than Christ crucified and glorified, that it is only by starting there we will end up in the right place. In the same vein, the panel also reminded us of Metropolitan +ANTHONY Bashir’s insistence that, once love is manifested, all things are possible.

All of these things are worth thinking about, and I encourage you all to do so as well.

More to come on Day 2.

—

Day 2: Again, too much to summarize in one e-mail, but a small handful of highlights:

First two presentations this morning were from Fr. Ephrem Lash, who looks and sounds like Gandalf as portrayed by Ian McKellen (and who has a wonderful website, http://www.anastasis.org.uk), who is also a scholar from England (I believe he is a colleague of Bp. KALLISTOS Ware, but I could be mistaken) who has quite a bit to say about translations of the Bible and liturgical texts into English, and Mark Bailey, instructor of liturgical music at St. Vladimir’s. The topic for both was the fittingness of English as a liturgical language, the necessary approach to translating texts, and then how best to set these texts to music so that a) the meaning is communicated and b) the musical tradition is carried on. Both had wonderful things to say about the necessary principles to make these things work. Before the first presentation, we sang “O Heavenly King”, and Fr. Ephrem noted that the setting took the word “impurity” and placed the stress on the last syllable, making it “impuriTEE”. “In the language I speak, English, it’s pronounced ‘imPURity’,” he observed. Mark Bailey had all kinds of fantastic practical examples of good text-setting and bad text-setting, and further suggested, “We’ve gotten our parishioners and singers too used to bad settings, and they’ve become attached to them as a result.” Fr. Thomas Hopko then commented, “Most of our churches are just copying what they’ve heard on recordings. Can we put out new recordings that do it the way you’re talking about?” Something to think about.

The second morning session consisted of presentations from the various heads of jurisdictional sacred music departments as to what they’re up to–Chris Holwey from the Antiochian Archdiocese, David Drillock from the OCA, and Vicki Pappas from the Greek Archdiocese. While interesting, I found it fascinatingly unnecessary to have such redundancy. All three of them are essentially doing the exact same job, providing the exact same resources in exactly the same manner. One fervently hopes that eventually there will be no need for multiple separate departments of sacred music.

The afternoon panel I attended was on the topic, “Educating Liturgical Musicians in the 21st Century.” Vladimir Morosan, a musicologist who specializes in the Russian repertoire, was the moderator. He framed the panel discussion by asking, “How do we explain that the oldest and richest singing tradition in Christendom does so little to formally prepare liturgical musicians? What do we do about it?”

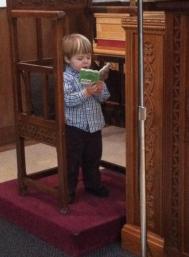

Anne Schoepp, a choir director in the OCA in California, argued passionately that Orthodoxy is a singing culture, and we need to do everything we can at the parish level to start our kids singing and to get them used to singing and loving singing. Fr. John Finley of our own Archdiocese suggested that the model of the Classical School that is starting to pop up in Orthodox circles could be a way to disseminate this kind of curriculum; I suggested that there’s an even more obvious answer, the tradition of the choir school as it still survives in England and even some places here in the US like the St. Thomas Choir School in New York and the Cathedral Choir School at the Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake City. “Let’s talk,” Fr. John said.

However we do it, the panel continued, people need to be immersed in good liturgy in order to be able to do good liturgy–it must be soaked in, the liturgical aesthetic must be ingrained in us. To this end, one panelist said, the power of the priest cannot be underestimated in terms of cultivating potential–kids as well as adults need to come to events like this, for example.

After the afternoon panel was choir rehearsal; Mark Bailey is very exact, and it’s a real learning experience to watch him conduct. It continues to be something else having a 100-voice choir singing in a church where the acoustics are as favorable as they are here. Then Vespers, where a small ensemble sang the stichera and whatnot, not dissimilar from what usually happens at All Saints.

After dinner was a concert performed by a group called the St. Romanos Cappella (as opposed to Cappella Romana, a completely different ensemble), singing a program entirely of music by modern Orthodox composers–all but one of whom were in the audience. Tikey Zes (who composed our All Saints troparion), Ivan Moody, Kurt Sander (formerly of Indiana University Southeast), James Green (the one not in attendance), Mark Bailey (man, the guy is everywhere), and Fr. Sergei Glagolev. Each one of them brings something different to the table, but it was all wonderful. It would be nice to learn several of these (particularly the Glagolev, Sander, and Bailey material), because it would be a shame to have all of this beautiful music out there representing a living continuation of the tradition and then have it never actually be sung in our churches. It would also be especially nice to finish learning Fr. Sergei’s setting of Psalm 103/104 for Vespers; now having heard what it actually sounds like in a church and not just on a recording, I’m more convinced of this. (And Bp. MARK already approved it back in December, which is handy.) Besides Psalm 103/104, they also sang one of his settings of the Cherubic Hymn, the Anaphora, the Megalynarion, and the Alleluia before the Gospel (including the refrains), and it was made very evident what a treasure trove his liturgical music actually is. He received a standing ovation at the end of it–surely every composer there deserved one, but he was quite appropriately the man of the hour. It was very moving.

After a looooooooooooooooooong, far-reaching conversation with Dn. Kevin Smith, choirmaster at St. Vlad’s, we managed to miss the shuttle back to the hotel and had to get a ride back from a Bulgarian woman named Danielle. And now it’s time for me to fall over and go to sleep. More to come tomorrow.

—

Day 3: There was a lot of theoretical stuff talked about today. I found it fascinating, but there’s little I can just summarize into an anecdote. Mark Bailey again had interesting things to say on a variety of topics; one issue he described was that of a common faith not necessarily uniting the Orthodox into a common sense of heritage. In terms of what that means musically–well, for many of us who are converts, “all Orthodox music is music for all Orthodox”, but that’s a very unique attitude to some (by no means all) American converts. He noted that in Russia right now there’s an argument over what kind of liturgical music from their various indigenous traditions (common chant, znamenny, etc.) will adequately represent the Russian culture. In this country, we have the opposite problem–we as yet have no indigenous Orthodox musical tradition, and so are trying to determine what bits and pieces from other national practices will best express Orthodoxy as it exists in America. Do we do a little bit of everything and make it a “checklist”-style approach? Do we pick one thing–Byzantine chant, Russian 4-part chant, whatever–and try to make it our own?

Mark Bailey is really big on liturgical singing doing no more and no less than supporting the liturgical action. That is, that liturgical singing either prepares for, accompanies, or is a liturgical action or rite. To do something other than one of these three things is, therefore, not liturgical and therefore spurious as far as this context is concerned. To that end, he says, musical form should elaborate on, and therefore draw the member of the congregation in to, a sacred action. At the same time, David Drillock two days ago reminded us that a large part of what we do is “proclamatory”–the exact opposite of drawing somebody in. I’m coming to the conclusion after hearing all of this discussed for two days that, as is so often the case in Orthodoxy, it cannot be “either/or”–it must be “both/and”. Part of its musical beauty come from the way in which the liturgical event is supported, and part of its ability to support the liturgical event must come from its beauty.

See what I mean about a lot of theoretical stuff?

One really practical thing he said with which I really agree is the idea that we need to not turn antiphons into anthemic pieces–they are a liturgical dialogue, not a big choral moment. What does that mean for us at All Saints? I don’t know yet; as it is we have a soloist sing the verse followed by the choir singing the refrain. What about this–rather than soloist plus choir, maybe it’s something like having the men intone one verse, the choir sings the refrain, the women intone the next verse, choir sings the refrain, etc.? We will play with possibilities at future rehearsals.

The afternoon panel, “Where do we go from here?” was interesting. People talked about a number of things, from PSALM formally getting behind issues like jurisdictional unity and a standardized English translation, to spearheading an English musical setting of the entire Octoechos (using, of course, this as-yet nonexistent “American chant” as the medium), to devising a music curriculum for use in parish schools. I think there are all kinds of things we can accomplish, we just need to think big. One of the issues, of course, is that in the past it has been possible for these issues to be solved in a “top-down” manner; the patriarchate or synod or whatever ruling body standardizes the practice/text/chant/whatever and promulgates it. The reality in this country, however, is that we’re having to solve many of these problems from the grassroots level on up. There’s a lot of “rolling our own” that takes place (as I found out earlier this week when I thought I needed a hierarchical “Before Thy Cross” and couldn’t find one to save my life), simply by necessity, because if we don’t do it, nobody else will.

Vespers was lovely. The large conference choir sang everything, and it was something. Being able to worship together (and commune together, tomorrow morning) is what makes this more than just a conference.

The evening panel, on composing liturgical settings for the English language, was made up of Ivan Moody, Fr. John Finley, Fr. Ephrem Lash, Mark Bailey, Fr. Sergei Glagolev, Vladimir Morosan, Tikey Zes, and Nicolas Resanovic. All I can say is–to have all of these people in one room was simply stunning. Not just their brilliance and talent, but their clear love for God and the Church as well. Ivan Moody provided a deft touch of dry, droll Englishness as the moderator. He provided a wonderful quote from St. John Chrysostom: “The tongue is made holy by the words when spoken by a ready and eager mind.”

There was a question where somebody described the situation of somebody coming up to the kliros or into the choir and being told, “Here’s the music for this service. We don’t actually do it that way, but here’s the music.” Big understanding laugh from the audience.

There was a fascinating moment where someone stood up and said, “You know, I’m from the Deep South. The South is a ripe field for Orthodox evangelism–the people there are crying out for the truth. Culturally, however, if we don’t bring it to them in English, their English, they are not going to care what we have to say.” This prompted Mark Bailey to remind us that, in this country, we are a missionary church with a missionary imperative, and that must inform what we do musically.

And then that, as they say, was that.

—

Day 4: Day 4 was short and sweet. With a 7:30am Matins service, I had to wake up at 6 to check out of the hotel. They did Matins and Liturgy as separate services, as opposed to Matins running right into Liturgy. There was a pause of a few minutes as Mark Bailey got set up to conduct the conference choir, and as the octet (into which I was roped) got into our places.

I may quibble with some (but by no means all) of the settings that were selected (I’ll be honest–the Russian chant in English is very jarring to my ear), but I have to say, having that 150 piece choir singing most of it and getting to sing in the octet that did the rest, in that church, with that conductor, was absolutely something else. I wish you all could have been there to take part, and my hope is that when this happens again, perhaps more of us can go. Fr. John Finley celebrated and homilized; it being the Pre-Feast of the Transfiguration, that was his topic. He started out with the quote from the Gospel reading, “It is good to be here.” It was quite apt. He exhorted us to “embrace the struggle” that we have adopted over the last few days, which was well-taken.

And that was that, more or less. There were some parting remarks at breakfast, and I think a lot of people are coming away from this event feeling like it was something seminal, that there has been good seed sown. Time will tell how God’s hand is in all of this, but one way or the other, it seems that the conference has exceeded everybody’s expectations.

A funny anecdote and a really cool thing: I went up to Fr. Ephrem Lash (the priest who looked and sounded like Ian McKellen’s Gandalf) and asked for a blessing. He sized me up and said (you’ll have to imagine the Ian McKellen-like voice), “Young man, did you receive Holy Communion this morning?”

“Yes, Father.”

“You never ask for the priest’s blessing after receiving Communion. You never ask for a blessing or kiss an icon. You have the Lord inside of you, so what can they possibly add? The Russians and the Arabs have gotten very bad about this.” I took it in stride, because I’m aware that it is an issue where there is not uniformity of practice or opinion. It was funny nonetheless. I then told him that I found his talk very edifying and he said, “Ah, ‘edifying.’ I never mean to edify, my boy; I only wish to make people laugh.”

So there we have it. Thanks for reading my ramblings; I just wanted to make sure that you all knew for sure I was where I said I was going to be, and hadn’t just taken off for Hawaii or something for a few days. If anybody wants to know more about anything I’ve talked about (or anything I haven’t, for that matter), let me know, I’d love to talk about it, particularly now while the memories are all still fresh.

In Christ,

Richard

Well, the spike in traffic the last few days leads me to believe that maybe the idea of an Orthodox choir school has drawn the attention of more than my usual two readers. Cool. If that’s so, then let me go into some more detail, and let me suggest a course of action.

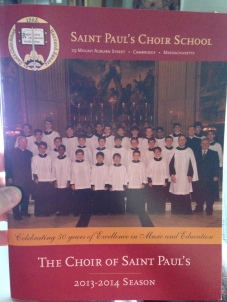

Well, the spike in traffic the last few days leads me to believe that maybe the idea of an Orthodox choir school has drawn the attention of more than my usual two readers. Cool. If that’s so, then let me go into some more detail, and let me suggest a course of action. Something that, alas, I can’t link to but that you should be able to acquire if you want a copy, is the 50th anniversary season brochure for St. Paul”s Choir School. They have them out for the taking in the narthex at St. Paul’s; I got a copy when I went to their Christmas concert on Friday. If you contact the school and ask for one, I have to imagine they’ll send it to you.

Something that, alas, I can’t link to but that you should be able to acquire if you want a copy, is the 50th anniversary season brochure for St. Paul”s Choir School. They have them out for the taking in the narthex at St. Paul’s; I got a copy when I went to their Christmas concert on Friday. If you contact the school and ask for one, I have to imagine they’ll send it to you. Since I’ve just run a couple of posts that have touched upon the topic of choir schools, and last week I had occasion to run the pitch — such as it presently is — past a couple of friends, maybe I can take a moment to go into detail about how I could see an Orthodox choir school coming together.

Since I’ve just run a couple of posts that have touched upon the topic of choir schools, and last week I had occasion to run the pitch — such as it presently is — past a couple of friends, maybe I can take a moment to go into detail about how I could see an Orthodox choir school coming together.