Well, the spike in traffic the last few days leads me to believe that maybe the idea of an Orthodox choir school has drawn the attention of more than my usual two readers. Cool. If that’s so, then let me go into some more detail, and let me suggest a course of action.

Well, the spike in traffic the last few days leads me to believe that maybe the idea of an Orthodox choir school has drawn the attention of more than my usual two readers. Cool. If that’s so, then let me go into some more detail, and let me suggest a course of action.

First of all, thanks for all of the positive reactions. It’s great to see that there’s a way to describe this vision so that people get it and get excited about it; I hope that this is a sign of things to come. Please continue to share these posts far and wide; it’s an idea that has to gain a certain critical mass before it can go anywhere besides this blog.

Also, there have been a number of excellent suggestions that have come from my “Orthodox choir school: how I’d do it” post. Suggestions about cities, about teaching methods, about other schools to look at, and so on. I appreciate all of that, and I’m all ears for that kind of input. When (I repeat, when) the time comes, that will all be extremely useful — keep it coming!

Something that has been brought up is that there have been people who have toiled in Orthodox children’s music education for years, and there are existing programs that struggle to stay afloat. Wouldn’t it be better to try to build everybody up rather than concentrating efforts in one location? Might putting all the eggs in one basket be a well-intentioned, but ultimately misplaced, idea?

I had a response to this, but before I go into that, I want to make everybody aware of some valuable resources that should be looked at if this subject is going to be taken seriously. There is the Choir Schools’ Association in the UK, and they have a document titled “Reaching Out”, which is a great overview of the current state of the tradition in England. One is a doctoral thesis by one Daniel James McGrath titled “The Choir School in the American Church: a study of the choir school and other current chorister training models in Episcopal and Anglican parishes”. There’s also a doctoral thesis by Lucas Matthew Tappan, “The Madeleine Choir School (Salt Lake City, Utah): A Contemporary American Choral Foundation”.

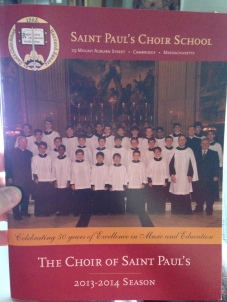

Something that, alas, I can’t link to but that you should be able to acquire if you want a copy, is the 50th anniversary season brochure for St. Paul”s Choir School. They have them out for the taking in the narthex at St. Paul’s; I got a copy when I went to their Christmas concert on Friday. If you contact the school and ask for one, I have to imagine they’ll send it to you.

Something that, alas, I can’t link to but that you should be able to acquire if you want a copy, is the 50th anniversary season brochure for St. Paul”s Choir School. They have them out for the taking in the narthex at St. Paul’s; I got a copy when I went to their Christmas concert on Friday. If you contact the school and ask for one, I have to imagine they’ll send it to you.

Nota bene — with all of these resources, one has to make sure that one takes them mutatis mutandis to a certain extent. McGrath and St. Paul’s are dealing with a context of boys’ choirs, and I’m talking about a co-ed approach, for example. The Madeleine Choir School and St. Paul’s are Catholic, and McGrath is writing from an Anglican perspective. Nonetheless, all are extremely useful in terms of how they talk about organization, curriculum, challenges, and so on — Tappan in particular explicitly has the objective of serving as a “road map” (his words) for those who might want to follow the Madeleine’s lead. Handy, that.

One of the main things I want to put forth here is this passage from Tappan’s thesis on the Madeleine as the justification for a choir school:

…a choir school consists of an institution where children are given a well-rounded musical education as well as liturgical formation in the ars celebrandi, and where they put these skills at the service of the sacred liturgy on a regular basis within a specific community (often that of a cathedral or collegiate chapel). In return, these children are given an outstanding elementary and religious education.

Even though these qualities constitute the basic elements of a choir school, each institution is a unique place where the choir school tradition exists within a particular time and culture… Perhaps the church musician will find in the choir school a model for training young people in an art that has the power to transform lives and to bring many out of the isolation of modern living into a living community of musicians and believers, forming young musicians “for the lifelong praise and worship of God” (p. 2).

But then there’s the epiphany of Gregory Glenn, the founder of the Madeleine Choir School, when he spent three months at Westminster Cathedral Choir School in London:

What Glenn realized was that the institution itself was the formator (emphasis mine). The incessant rounds of daily rehearsals and liturgies in the cathedrals and the process of going through a massive amount of repertoire year after year was crucial to being able to sing, for example, a Poulenc Mass on short notice. The choristers sight-read so easily that rehearsal time was never spent learning notes. There might be a false note or two the first time through a work, but the boys usually corrected themselves the second time around. Choir masters were able to spend the majority of rehearsal time working toward a more musical performance of the repertoire. According to Glenn, the Madeleine Choir School is still working toward this goal, but it becomes more of a reality with time. (Tappan, p. 26)

Here was my answer to the concern about concentrating efforts in one location:

I spent 11 years in a location that was, theoretically, fairly central in the United States, but as far as Orthodox Christianity went, was about as isolated as you could be without being in Wyoming. Almost anything and everything the parish there took on could be (and often was) fairly described as “being a lot of effort for one location”, right down to building a church. It still needed to be done. Along the same lines, the Madeleine school is certainly “a lot of effort for one location” (in Salt Lake City, no less!), but it’s still worth doing.

The other thing I’ll say is that musical efforts in particular often get problematized in “American Orthodoxy” (whatever we mean by that) as “reinventing the wheel”, that reduplication of effort doesn’t accomplish anything… What needs to be recognized is that not all wheels will travel on the same roads[…], people and institutions need to play to their strengths, and dispersion of effort that hangs everything on the energies of either one person or a tiny handful of people is a disaster waiting to happen. The Madeleine Choir School is not the only Catholic school in the Salt Lake City metro area, for example, but its existence allows for the faculty and students to play to a particular set of strengths, and the result is an example that is inspiring. Supporting music education in existing Orthodox schools is a great thing to do, but it also seems to me that establishing a model school that focuses particularly on that aspect will allow for a level of excellence to develop and be made manifest publicly. I think we accomplish a lot more when we’re able to work together than when we’re isolated; my experience is that most of us Orthodox musicians are too isolated from each other as it is, and that that is a bad thing.

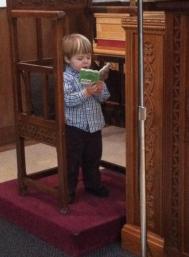

Beyond that — as I said earlier, I attended a Christmas concert sung by the choirs of the St. Paul’s Choir School Friday evening with Megan and Theodore; one of the big takeaways was that Theodore was absolutely enrapt when the boys processed in, wearing black cassocks and singing “One in Royal David’s City”. I’ll say that the evening was was mostly the work of the the preparatory choir (the main choir had their big concert yesterday with Britten’s “A Ceremony of Carols”), but everybody did something, and they’ve got a good thing going there.

So, where to, folks? How do we get there from here? I’ve told you how I’d do it — and, I have to say, it’s remarkably similar to what Tappan describes Gregory Glenn, the Madeleine Choir School’s founder, as having done (and I discovered Tappan after I wrote that post) — he put a great deal of time in visiting model institutions and putting together a feasibility study/planning document with a proposed budget. Realistically, I think this is going to be somebody’s full-time task for at least six months.

My modest proposal, then, is this — a great Christmas gift to me, to your kids, and to our Church, would be a gift in support of this initial effort. Somebody shared the post saying, “I wish I had a million or two to give to such an undertaking”; well, it doesn’t need a million or two, not yet, and while you might not be in a position to give a million or two, maybe you can do something (particularly since it’s near year-end — taxes are coming!). It doesn’t really matter how much you might be able to do; if everybody who saw my posts over the last week even gave something relatively small, it would go a long way towards making this possible. Anyway, I don’t want to do a hard sell on giving right now. Rather, this is just the trial balloon — the question is, can we fund the initial planning activities, yes or no? You tell me. If we can, then maybe we can do this for real.

The way to give is through The Saint John of Damascus Society; click here, click on the donate button, and you’ll be taken to PayPal. The Society is a tax-exempt (501(c)3) non-profit, so all gifts are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. If you want to do something but don’t want to do it via PayPal, drop me a line at richardbarrett AT johnofdamascus DOT org.

I’m really not interested in asking for money right now, so we’re clear. This isn’t about money to me. At the same time, without some money, the next steps are really out of reach.

This is an open forum on the topic, so please, any questions, suggestions, comments, requests for more information, anything — keep it coming! And if you want one of the The Choir DVDs, e-mail me with an address.

Okay, my friends. I’ve made my pitch. You’ve all told me you’re interested and supportive; pray for us, tell me what we’re doing next, and share this far and wide if this is important to you. Thanks for sticking with me so far.

Since I’ve just run a couple of posts that have touched upon the topic of choir schools, and last week I had occasion to run the pitch — such as it presently is — past a couple of friends, maybe I can take a moment to go into detail about how I could see an Orthodox choir school coming together.

Since I’ve just run a couple of posts that have touched upon the topic of choir schools, and last week I had occasion to run the pitch — such as it presently is — past a couple of friends, maybe I can take a moment to go into detail about how I could see an Orthodox choir school coming together.

The Choir

The Choir