A few months ago, an opportunity came up to pitch an essay explaining the relevance of my subject area to a public audience. I made a pitch about Byzantine history, the editors liked the pitch, and I wrote a draft. Two drafts later, even cutting the things they asked me to cut and changing the things they asked me to change, it became clear that what I was trying to say wasn’t working for the forum as the editors envisioned it; from my perspective, what they wanted was an apologia for Byzantine history that somehow strictly avoided any actual discussion of Byzantine history or the perspectives of current scholars in the field, and I rather feel like their objections to what I wrote only proved the point I was trying to make.

Oh well; the beauty of having a personal blog is I can put up whatever I like, so I’ve thrown back in a lot of the things they asked me to take out, updated it a little bit more, and I present it to you here. Doubtless the audience will be much smaller, but whatever. It’s Akathistos Saturday, and I discuss the modern significance of the events commemorated therein in this essay, so it seems appropriate to publish it today. Enjoy.

—

The word “Byzantine” is pejorative in the vast majority of English-language contexts. As a Byzantine historian, this always leaps off the page at me, and it strikes me that our conceptions and misconceptions about the distant past influence our attitudes towards present-day matters. Recent citations provides no shortage of examples.

- Consider a 22 January 2015 headline from the Canadian newspaper National Post: “Shawn Rehn case shows Byzantine criminal justice ‘system’ built to avoid accountability.” In the body of the article itself one finds the declaration that “A lot of facts can’t be established in the… case because the paperwork… is Byzantine and emanates from multiple arms of the beast that pretends to be a system.”

- For example, a 26 January 2015 Huffington Post piece by Rebecca Orchant on the settlement between The Hershey Company and an import company that effectively prohibits the import of several brands of chocolate made overseas, in which Orchant, a retailer, says that her choices now are to “turn to more Byzantine measures to get our British chocolate, or sell an inferior product.”

- There is also a Heritage Foundation report from 26 January 2015 titled “Reforming DHS: Missed Opportunity calls for Congress to Intervene,” which calls the oversight of the Department of Homeland Security not just “byzantine” but “balkanized and dysfunctional”.

“Byzantine”, for these writers, means overly ornate, unnecessarily — but possibly intentionally — complicated, corrupt. The Heritage Foundation juxtaposes it with “balkanized”, another geographic term (describing a former portion of the Byzantine Empire) that has been turned into a pejorative, here meaning a whole divided into small, mutually-opposed parts.

“Byzantine”, in fact, is a word that the so-called “Byzantines” did not use to describe themselves; “Byzantium” was the old name of the port town on the Bosphorus at the intersection of eastern Europe and Asia Minor where the Roman emperor Constantine decided to establish his new capital city in 325. He called it “New Rome”, it came to be known as Constantinople, “Constantine’s City”, today known as Istanbul (probably from the Greek phrase eis tin poli — “to the city”). While Romulus Augustus, the last Roman emperor in the West, abdicated to Germanic forces in 476, by that point the Roman Empire had re-centered itself around Constantine’s capital. Eventually its borders began to shrink irrevocably, but nonetheless, the transplanted eastern empire survived in one form or another until 1453, when the city fell to the Ottomans.

For a Byzantine historian in the West, the pejorative use of “Byzantine” in our vernacular represents a never-ending series of “teachable moments”, opportunities to examine the myopic privileging of the immediate present by our media at the very least, but also to interrogate the way various fields reflexively treat that which is “Eastern” as something inherently “foreign”, “mysterious” – or worse, “mystical”. That Byzantine history is by definition a pre-modern subject already guarantees its marginalization by the mainstream, but even among medievalists, it is not sufficiently “Western” for a discipline that tends to privilege Latin and French subjects, being situated in the “Greek East”. At the same time, it is also not really sufficiently “Eastern” for most historians who work with Middle Eastern or Far Eastern topics; Edward Said, for example, sees Christianity, even that of the “Greek East”, as being fundamentally “Western”.[1] These barriers can tend to ghettoize Byzantine issues, placing them off to the side in survey courses and textbooks. To the extent that the Byzantine world is talked about in those contexts, they are largely informed by biased Western sources — such as the tenth century Liutprand of Cremona, who after an embassy to Constantinople described the Emperor Nicephorus Phocas as “a monstrosity of a man… [and] in color an Ethiopian” dressed in royal robes that were “old, foul smelling, and discolored by age” — resulting in an Orientalizing overemphasis on the perceived differences between the “Byzantine east” and the “Latin west”. The discourse emphasizes the tawdry excess of supposed cultural discontinuities – aesthetics, politics, art, religion, and so on – and discusses them as misunderstood, abstract distortions rather than as concrete realities. The picture of the Roman East that emerges is really a straw man, representing everything that the we Westerners pat ourselves as having left behind after the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Enlightenment — ugly aesthetics that take the worst elements of the classical world and distort them, corrupt politics represented by the machinations of the monarchical emperors, a state-subject church that combines the most patriarchal and superstitious elements of paganism and Christianity. It is not a fully-qualified subject of interest in its own right; it is a gaudy red-headed stepchild of Western history cloaked in a cloud of incense.

Recent scholarship, thankfully, is showing that many of these characteristics, so distasteful to a Western intellectual ethos, are misunderstood and mischaracterized, such as the claim that Eastern Empire was an absolute imperial theocracy.[2] As well, an informed understanding of many of today’s pressing international issues — ISIS’ violence against religious minorities in Mosul and Libya, the civil war in Syria, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the complexity of Turkey’s application to the European Union, Greece’s economic woes, even elements of the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine — must acknowledge a sense of the sweep of history that includes, rather than dismisses, Byzantium.

To give but one example, the demonstration by tens of thousands of Muslims in front of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul on 31 May 2014 makes far more sense if you understand that what is today a museum was built by the emperor Justinian in the sixth century as the Empire’s largest church. This exemplar of Byzantine sacred architecture was the largest cathedral in the world for nearly a thousand years; it was repurposed as a mosque by the sultan Mehmed II after 1453, inspired sultan Ahmet I to build the so-called Blue Mosque as a copy just a few hundred meters away in 1609, and then was decommissioned and turned into a secular museum by Ataturk in 1934. Today, besides the Muslims who hope to persuade the Turkish government to re-open the monument as a mosque, there are Greeks who want to see the monument returned to the Greek Orthodox Church. Hagia Sophia may be little more than a museum to some, but it is a Byzantine foundation that still has considerable discursive power in 2015, resonating for present-day adherents of Islam and Orthodox Christianity, as well as being a symbol of two past empires for their would-be inheritors. The discursive weight of such symbols stretches far beyond modern-day Turkey, extending throughout the Mediterranean, Asia Minor, the Middle East, the Balkans, and Russia.

The recent episodes of violence by ISIS against Christian minority groups in Mosul and Libya are also rooted in chapters of Byzantine history. Coptic Christians, like those beheaded in Libya in February 2015, are the modern Christian group that count themselves as the present-day successors of the historic Church in Alexandria, Egypt. They were part of the Roman Empire in the East only to be separated ecclesiastically by theological disputes. Assyrian Christians, like those kidnapped in Tal Tamer on 23 February 2015, are the modern Middle Eastern Christian group that claims continuity with the so-called Church of the East or Catholicosate of Seleucia-Ktesiphon of antiquity, a Christian group that straddled the frontier between the Roman and Persian empires. They were cut off more because of geography and political boundaries than because of theological disputes. In the seventh century, both groups were permanently separated from the Byzantine mainstream by Arab invaders.

To say the least, this background is not at all well-understood by our media; even well-intentioned pieces, like Graeme Wood’s recent “What ISIS Really Wants” for The Atlantic, demonstrate serious ignorance in passages such as this, where Byzantium is nothing more than a transitional stage between ancient Rome and present-day Turkey, not even worth mentioning by name:

Who “Rome” is, now that the pope has no army, remains a matter of debate. But Cerantonio makes a case that Rome meant the Eastern Roman empire, which had its capital in what is now Istanbul. We should think of Rome as the Republic of Turkey—the same republic that ended the last self-identified caliphate, 90 years ago.

In terms of my specific area of research — I am writing a dissertation on public devotions to the Virgin Mary in Constantinople between the fifth and seventh centuries. The Byzantine image of the Theotokos, the Mother of God, is another kind of symbol with powerful religious and political resonance, and the memory of seventh century events associated with the Virgin are still present in today’s discourse. For example, on 22 April 2013, The New York Times reported that the Syriac and Greek Orthodox bishops of Aleppo were kidnapped in the village of Kfar Dael.[3] As of this writing, that situation has not been resolved, and tensions and violence have, obviously, continued to escalate otherwise there. In response to the kidnapping as well as the overall time of hardship, Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch John X gave a fascinating instruction in an encyclical for Orthodox Palm Sunday: “Let our [Palm Sunday] processions be this year with candles tied with black ribbons, chanting the hymn: ‘To Thee O Champion Leader…,’ instead of the hymn “Rejoice O Bethany…,” asking the Virgin Mary to keep our Church as a fortified city.”[4]

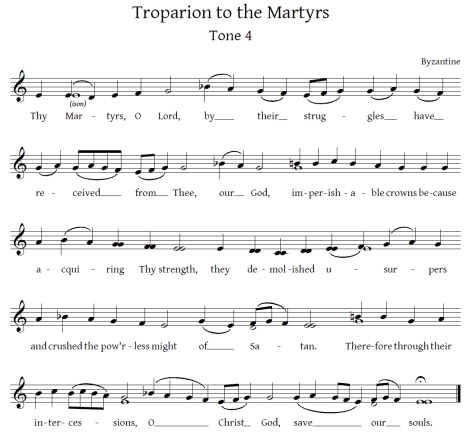

John’s instructions are rooted in matters of the Eastern Romans’ historical record. “To Thee O Champion Leader” refers to a seventh century hymn that was appended as a proemium to the beginning of a much longer hymn, a fifth century sung theological poem called the Akathistos (“not seated”, referring to the practice of standing while it is sung) hymn. The proemium was composed after Constantinople’s successful repulsion of the Avar attack in 626 with, according to some accounts, the Virgin Mary herself fighting on the walls of the city. It is a first-person statement of civic devotion and gratitude on the part of Constantinople itself to the Virgin:

To you, all-victorious general, I your city, O Mother of God, having been delivered from terrible things, ascribe to you thank-offerings of victory. But as you have invincible power, free me from all dangers, so that I may cry to you: rejoice, O bride unwedded.[5]

The entire text of the Akathistos has a particular liturgical relationship to the Lenten season that precedes Palm Sunday; during the five Sundays of Lent the proemium is sung during the Sunday Divine Liturgy (or Mass), and then the Akathistos hymn is sung three times in its entirety throughout the course of the Lenten season. However, by the time of Palm Sunday, the services are properly considered those of Holy Week rather than Lent, and the time for people to have “To Thee O Champion Leader” on their lips has passed.[6] Patriarch John’s instruction, then, is disregarding the liturgical season and instead looking back to the historical circumstances surrounding the proemium’s composition. Just as the Virgin was the defender of the City then, John is saying, Christians now in this time of crisis may make a point of singing this hymn to the Mother of God outside of its proper time to appeal to her as the defender of the Church, the heavenly city.

Late antique Constantinople’s explicit identification of itself as the Virgin’s city, then, is extended and repurposed for the present day in the context of a liturgical celebration of high solemnity,[7] with the population of Christians under Patriarch John now being the Virgin’s city. John is discursively engaging current circumstances through the liturgy, through music, through Orthodox Christianity’s own sense of late antique events as sacred history, and doing so in a way clearly focused on the person of the Mother of God and rooted in Constantinople’s devotion to her at the level of the city itself.

In conclusion, I would echo Dame Averil Cameron’s recent insistence that Byzantine history is in fact mainstream history, and that to treat it as otherwise is to treat it as “subaltern”.[8] I maintain that Byzantine history is not simply an irrelevant distorted mirror image of the West, a chapter best forgotten except when we need a pejorative to describe things that are helplessly tangled and complex, but in fact an area of inquiry that is vital to understanding the world in which we find ourselves today.

[1] E.g. Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1994; reprint, 2003), 59.

[2] Anthony Kaldellis, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

[3] Hania Mourtada and Rick Gladstone, “Two Archbishops Abducted Outside Northern Syrian City,” The New York Times, 23 April 2013 2013.

[4] Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and All the East John X, “Pastoral Letter,” (Our Lady of Balamand Monastery, Tripoli, Lebanon: The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, 2013).

[5] Akathistos, Prooemium II. Translation mine.

[6] For a discussion of the rubrics, see Archimandrite Job Getcha, The Typikon decoded: An explanation of Byzantine liturgical practice, ed. Paul Meyendorff, trans. Paul Meyendorff, Orthodox Liturgy Series (Yonkers: Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2012), 199-201.

[7] Ibid., 209-11.

[8] Averil Cameron, Byzantine Matters (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 115.

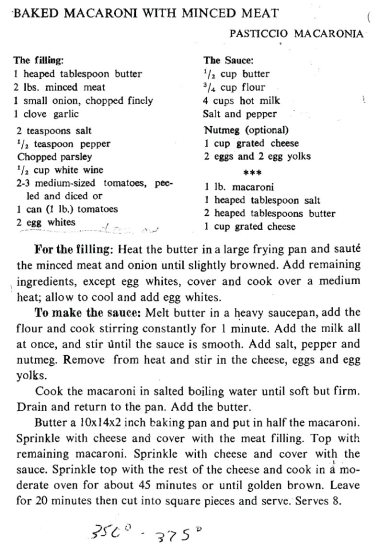

When Anna, Theodore’s nona, was first getting to know us back in fall of 2006, she asked us one day — “Can I come and make Greek food in your kitchen sometime?” Wow, twist our arms. What she made for us, and what she has made for us and others many times since, and what we also have learned how to make ourselves on a fairly regular basis, was pastitsio.

When Anna, Theodore’s nona, was first getting to know us back in fall of 2006, she asked us one day — “Can I come and make Greek food in your kitchen sometime?” Wow, twist our arms. What she made for us, and what she has made for us and others many times since, and what we also have learned how to make ourselves on a fairly regular basis, was pastitsio.

When I was about a year old to about four years old, we lived in a neighborhood of Anchorage called Geronimo Circle, near DeBarr Road in the northeast part of town. To our left was a neighbor lady named Nina, and to our right were the Slays — Larry, Bonnie, and their little kids, Ethan, who was my age, and Jenny, the baby. Ethan and I played together just about every day; he sent me to the ER with my first split lip for my first stitches (couldn’t tell you over what, except I remember something about a toy crane being involved); we built forts out of couch cushions; and so on. Bonnie and Larry were close to my parents, too, and I have a lot of happy memories of the bunch of us being at each other’s houses in those early years. Larry built me a few things in his woodshop that I remember fondly; there was a marble rack that I spent hours playing with, and then he also made me a chair when I was about three years old — carved my name in it, finished it, everything. My mom still has it, and I’d bring it home if it fit more easily in a suitcase.

When I was about a year old to about four years old, we lived in a neighborhood of Anchorage called Geronimo Circle, near DeBarr Road in the northeast part of town. To our left was a neighbor lady named Nina, and to our right were the Slays — Larry, Bonnie, and their little kids, Ethan, who was my age, and Jenny, the baby. Ethan and I played together just about every day; he sent me to the ER with my first split lip for my first stitches (couldn’t tell you over what, except I remember something about a toy crane being involved); we built forts out of couch cushions; and so on. Bonnie and Larry were close to my parents, too, and I have a lot of happy memories of the bunch of us being at each other’s houses in those early years. Larry built me a few things in his woodshop that I remember fondly; there was a marble rack that I spent hours playing with, and then he also made me a chair when I was about three years old — carved my name in it, finished it, everything. My mom still has it, and I’d bring it home if it fit more easily in a suitcase. I must comment on another passing — not as close, but painful nonetheless. Three years ago, at the 2012 Florovsky Symposium, Fr. Andrew Damick introduced me to one Matthew Baker, saying, “Someday soon, you’re going to be reading books by him.” Turned out we knew many of the same people, and I’ll never forget his shock of red hair, thick beard, bow tie, and tweed jacket, or his way of disagreeing with people that suggested an internal amusement at just how wrong his interlocutors could be.

I must comment on another passing — not as close, but painful nonetheless. Three years ago, at the 2012 Florovsky Symposium, Fr. Andrew Damick introduced me to one Matthew Baker, saying, “Someday soon, you’re going to be reading books by him.” Turned out we knew many of the same people, and I’ll never forget his shock of red hair, thick beard, bow tie, and tweed jacket, or his way of disagreeing with people that suggested an internal amusement at just how wrong his interlocutors could be.