Some friends the other night made a Moroccan chickpea stew for us. One of them said that he had altered the recipe a little bit with what he’d had on hand; I turned to Flesh of My Flesh and said, “See? He makes stew with what he has.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

I didn’t come here to tell you that.

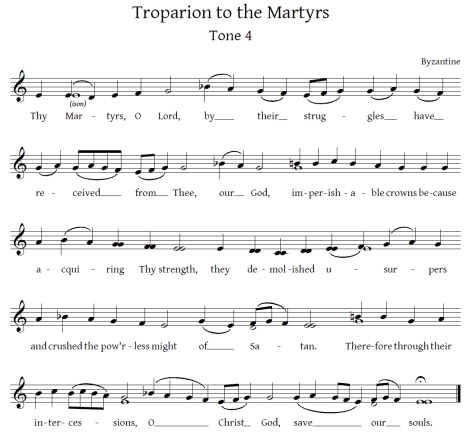

One of the topics I’m frequently musing about in this venue is, what does it mean to sing “Byzantine chant”, and how best to teach it to a variety of people? Specifically in terms of that variety — what might it mean to have a pedagogical approach that assumes some knowledge of how to do it, an approach that tries to convey best practices to a person knowledgeable about music, just not Byzantine music, and then, what would constitute a misguided approach that throws misunderstood elements together haphazardly? For illumination on this point, I turn to — strange as it may seem during the third week of Lent — pastitsio.

When Anna, Theodore’s nona, was first getting to know us back in fall of 2006, she asked us one day — “Can I come and make Greek food in your kitchen sometime?” Wow, twist our arms. What she made for us, and what she has made for us and others many times since, and what we also have learned how to make ourselves on a fairly regular basis, was pastitsio.

When Anna, Theodore’s nona, was first getting to know us back in fall of 2006, she asked us one day — “Can I come and make Greek food in your kitchen sometime?” Wow, twist our arms. What she made for us, and what she has made for us and others many times since, and what we also have learned how to make ourselves on a fairly regular basis, was pastitsio.

You can call it “Greek lasagna” if you like; many do, including Michael Psilakis. To do so is kind of like calling Syriac “the language of Jesus”, though; there’s a certain sense that it makes, but it’s kind of misleading, and it doesn’t acknowledge the dish on its own terms. Pastitsio has multiple layers of long, hollow noodles (ideally, Misko #2 Pastitsio Noodles) with a flour-based Béchamel-cheese sauce and a meat sauce. It’s a Greek comfort food to be sure; not exactly the dish one is talking about in a conversation about the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. All the same, my goodness is it delicious when made right, and a pan of pastitsio on the table is, in my experience, one of the best signs of a hospitable house, Greek or otherwise.

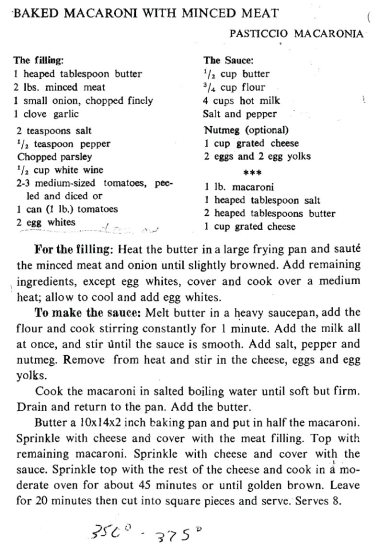

Like all dishes, there are regional, familial, and maybe even political differences. To the right is Anna’s foundational recipe, a pretty basic, classic version that allows for some variation based on what you have on hand and what you prefer. It’s nothing particularly fancy, and it doesn’t take that long to make. You could do this with beef, veal, or lamb; you could do it with whatever cheese you have handy (and it doesn’t make any particular suggestions where that’s concerned); and it’s not picky about pasta. Maybe it’s a recipe that assumes, if you’re a Greek person who already knows how to cook this, you’ll know how to take this and, mutatis mutandis, turn it into “the way YiaYia made it”. And, if you’re not, well, you’ll use what you have handy and you’ll make it work in your own way.

That’s one approach. There’s another way, somewhat more complicated, what we might call the “foodie” approach. Here is how Michael Psilakis frames the recipe in his cookbook, How to Roast a Lamb:

This is a classic Greek dish, which I often refer to as a Greek version of lasagna. You will need a deep, lasagna-style pan, and it may be hard to find the pastitsio noodles called for here. Try a Greek or Middle Eastern market or, of course, the Internet. The crucial thing is that the noodles be both hollow and straight, so you may substitute bucatini, perciatelli, ditali, or long, straight ziti laid end-to-end. This casserole, as with lasagna, must rest before serving to set, or it will be difficult to serve.

Okay, already there’s a different tone here. This is a recipe written for somebody who knows food, but maybe doesn’t know Greek food all that well (and there’s the “Greek version of lasagna” shorthand). He details the essentials, and tells you where you need to find them.

Ingredients:

- 3 tablespoons blended oil (90 percent canola, 10 percent extra-virgin olive)

- 1 large Spanish or sweet onion, finely chopped

- 3 fresh bay leaves or 6 dried leaves

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 2 pounds ground beef

- 1 1/4 teaspoons ground cinnamon

- Pinch ground nutmeg (optional)

- Pinch ground cloves (optional)

- 1/4 cup tomato paste

- 2 1/4 quarts water

- 1 (28-ounce) can plum tomatoes, crushed slightly, with all the juices

- 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

- 1 teaspoon sugar

- Kosher salt and cracked black pepper

- 1 (500-gram) package Misko Macaroni Pastitsio no. 2 (see above)

- 1 3/4 quarts Greek Béchamel Sauce (page 274, with eggs)

- 1 cup coarsely grated graviera cheese

And this is definitely a little different. Oil instead of butter (he goes into his reasons for cutting olive oil with canola oil earlier in the book; basically it’s a cost issue, and you can use all olive oil if you really want to), the seasoning is a little more robust (and more characteristic of a Constantinopolitan approach, perhaps), and he’s more specific about the meat, the noodles, and the cheese. Elsewhere he talks about possible substitutes for cheeses; gruyere is his principal recommendation. This is an ingredients list that wants to show an American cook how to be faithful to the model using the best of what’s available.

Going on:

Make the kima sauce: in a large, heavy pot over medium-high heat, add the oil and the onion with the bay leaves and cinnamon sticks for 3 to 5 minutes. Add the ground beef and brown thoroughly. Add all the spices and the tomato paste and stir for 1 to 2 minutes. Add the water, tomatoes, vinegar, sugar, about 2 tablespoons of kosher salt, and a generous grinding of pepper. Bring to a boil.

Reduce the heat, partially cover, and simmer for 65 to 75 minutes. Skim off the fat once or twice. Reduce until the sauce is almost completely dry. Proceed with the recipe, or cool and refrigerate.

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. In a large pot of generously salted boiling water, cook the macaroni until almost tender, a minute or so before the al dente stage. Drain well. Spread 1 cup of the Greek Béchamel Sauce on the bottom of a deep roasting pan or lasagna pan, and sprinkle with 1/3 cup graviera. Lay half of the noodles out on top of the béchamel. You should have 2 to 3 layers of noodles. Spread another cup of the béchamel over the noodles, without disturbing the direction of the noodles, to bind them. Scatter with 1/3 cup of the graviera. Spoon all of the kima sauce over the top and smooth flat. Spread 1 more cup of the béchamel over the kima sauce, scatter with 1/3 cup graviera.

Layer remaining pasta noodles over the béchamel. Spoon on the remaining béchamel and scatter with the remaining 1/3 cup of graviera. Bake uncovered until crusty, golden, and set, about 1 hour. If you don’t have a convection oven, you may want to increase the heat to 400 degrees F at the end, to brown the top. Cool for at least 40 minutes, to allow the custard to set so that the squares will remain intact when you cut them. Or, cool to room temperature, then refrigerate overnight.

And since he gives it its own recipe, here’s the Béchamel sauce:

Greek béchamel differs from French béchamel or Italian besciamella due to the inclusion of whole eggs. When a dish is baked, the eggs in the sauce create a custard. This basic ingredient is what makes many Greek dishes so special. Because of the large quantity of flour and the resulting thickness of the roux, you really can’t step away from the stove while you are preparing the sauce. Plus, you’ll need muscle to stir it thoroughly.

Ingredients:

- 5 ounces unsalted butter

- 10 ounces all-purpose flour

- 1 1/2 quarts whole milk, warm

- 2 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

- Large pinch nutmeg, preferably freshly ground

- 1 1/2 to 2 teaspoons kosher salt

- Cracked black pepper

- 5 large eggs, lightly beaten

In a large heavy pot, melt the butter over low heat, whisking with a large balloon whisk. Add the flour and whisk to a very crumbly roux, not a smooth paste. Whisk constantly and energetically or about 5 minutes to cook off the raw flour taste, but do not allow to brown (slide the pot off and on the heat every now and then if you sense it is getting too hot).

Still whisking constantly, drizzle in the warm milk until smooth. Continue cooking, adjusting the heat as necessary to keep the mixture at a very low simmer, until very thick. Whisk in the cinnamon, nutmeg, kosher salt to taste, and a generous amount of pepper.

Scoop out about 1/4 cup of the warm sauce. In a bowl, whisk the sauce into the eggs to temper them. Remove the pan from the heat and whisk all the egg mixture back into the béchamel.

Dude. I’m hungry. Maybe I shouldn’t be writing this during Lent. Dang it all.

Anyway, some observations — first and foremost, this is not the quick ‘n dirty way to make pastitsio. The meat sauce, I can tell you from experience, takes more like 2-3 hours to reduce than the 65-75 minutes advertised, at least on the stoves I’ve used. At the same time — oh my goodness is the end result amazing and flavorful (such that Anna now uses Psilakis’ meat sauce in combination with her foundational recipe). Now, if you want to shave off time, just skip adding the water. With the basic recipe, if you know what you’re doing you might elaborate the bare bones instructions somewhat; by contrast, here, if you’re familiar with the dish, then you might simplify this version a bit. Both recipes, in the end, faithfully (I hate the word “authentically”) reproduce what is understood as “pastitsio”; one does so by presenting a basic, easy to reproduce (and vary) method, and the other does so by breaking the dish down and building it back up using the language and ingredients of American foodie culture.

Now, you can have an argument over just how “Greek” pastitsio is. Real Greeks didn’t use Béchamel sauce until a hundred, hundred and fifty years ago, one argument might go. There’s something there with the meat sauce and the cheese and the noodles, maybe, but Béchamel? That’s an Italian or French corruption, not Greek.

You might also have a conversation about some of the details. There are pastitsio recipes you can find that are adamant that no real pastitsio ever has had any kind of cinnamon or nutmeg or anything else in the meat sauce, because it doesn’t need it, period, and that’s not how YiaYia did it, dammit.

However, what you’re probably not going to have much of a disagreement about is whether or not this recipe is pastitsio:

- 1 lb. lean ground beef

- 1 small onion, chopped

- 1 jar (24 oz.) spaghetti sauce

- 2 Tbsp. red wine vinegar

- 2 Tbsp. butter

- 1-1/2 cups milk

- 1 cup plain nonfat Greek-style yogurt

- 1/4 tsp. ground nutmeg

- 2 cups elbow macaroni, cooked

- 1/4 cup DI GIORNO Grated Parmesan Cheese

BROWN meat with onions in large skillet; drain. Stir in spaghetti sauce and vinegar; simmer on low heat 15 min., stirring occasionally.

MEANWHILE, melt butter in large saucepan on low heat. Add milk; bring to boil on medium heat, stirring constantly. Simmer on low heat 3 to 5 min. or until thickened, stirring frequently. Remove from heat. Stir in yogurt and nutmeg. Add macaroni; mix lightly.

HEAT oven to 350ºF. Spread meat sauce onto bottom of 13×9-inch baking dish; top with macaroni mixture and cheese.

BAKE 45 to 50 min. or until macaroni mixture is heated through and top is lightly browned.

Um, no. No, no, no, no, no. You want to insult a Greek person? Put this in front of them and call it “pastitsio”. This is beyond parody, really. This is macaroni and spaghetti sauce layered with yogurt and had some cheese sprinkled on it; no Béchamel, no attention to cheese, no nothing. This is a clueless American who vaguely remembers that there was a dish he had at a Greek festival or something that had noodles, meat sauce, some white stuff, and maybe a pinch of spice in it, making something up that sort of fits the general description, and adding “Greek yogurt” (nonfat? That’s not Greek yogurt, folks) and nutmeg to justify claiming that it’s “Greek food”.

And, here’s the thing — by this point, pastitsio has been made at Chez Barrett a sufficient number of times that it isn’t really “Greek food”. It’s just “food you’re likely to eat when you’re a guest of the Barretts”. Or, for that matter, when we’re your guests; I made Psilakis’ recipe for Christmas Eve dinner one year at my mom’s house. Call it trying to pass on the tradition.

Okay, back to the question raised at the outset about Byzantine chant. How might the analogy of pastitsio be applicable here? What’s the equivalent of Anna’s foundational recipe, what’s the equivalent of Michael Psilakis’ recipe, and what’s the equivalent of the Kraft recipe?

Well, what are the fundamental ingredients of Byzantine chant, and what’s variable for, shall we say, ingredients that one has on hand? For present purposes, maybe we’ll say that the fundamental ingredients of Byzantine chant are:

- it is a cappella,

- it is monophonic (that is, not harmonized by multiple voices),

- it employs drone that does not function as a harmonic bass line,

- it employs a sacred text, drawn predominantly from the liturgical cycle of the Orthodox Church,

- it employs the system of Byzantine modes, a centuries-old musical system with which the modern theoretical understanding as described by Chrysanthos of Madytos and clarified/affirmed by the 1881 Musical Committee of the Ecumenical Patriarchate is in continuity,

- the melodies are composed formulaically — that is, there is a vocabulary of musical phrases (theses) proper to each mode, and the composer formulates compositions according to this vocabulary of phrases so as to fit the accentuation and rhetoric of the sacred text appropriately and in the intended musical texture (fast, slow, syllabic, melismatic, etc.),

- and the melodies are notated using psaltic, or Byzantine, notation, and the notation is meant to be interpreted via a layer of oral tradition absorbed from one’s teacher.

Now, I’ve phrased much of that carefully. Not all Byzantine chant necessarily employs a liturgical text; there are examples that set paraliturgical poetic texts. The description of Byzantine modes allows for some leeway depending on local tradition; Lebanese and Syrian cantors might do certain things differently, as might some Romanian cantors. It also allows for a way of talking about medieval repertoire that was composed before Chrysanthos or the 1881 Committee. The point about notation might perhaps be controversial to some, but I would leave it there, simply because, as a prosodic and musical system intended specifically for that purpose, psaltic notation is the symbolic system that best expresses the musical and hymnographic repertoire we call “Byzantine chant”.

So what are ingredients that might be variable? Language, certainly; there’s nothing in that list that says that anything has to be in Greek or Arabic. It might be a lone man’s voice singing; it might be a choir of women. The point about oral tradition suggests that there is some level of acceptable variation of interpretation in some cases. There are different genres of hymns you can compose and sing within this framework; anything from quick, short, declamatory, syllabic hymns to long, slow, drawn-out compositions.

And, certainly, there are lots of arguments about some of the details. This, that, or the other musical development in the repertoire isn’t “really” Byzantine music, but rather a corruption arising from Turkish influence. No cantor who knows what they’re doing would ever sing this phrase the way you just did it. Some would argue that language actually isn’t an acceptable variable, at least not the way described above; it either has to be in Greek, or it has to adapt a Greek original in a way that favors the Greek version over the target language of the translated text at every point. Alternately, language may be generally variable to an extent, but there’s no way no how English is an acceptable language for this music. That kind of thing.

Whatever details one might argue about, however, here’s an indisputable example of a composition that is identifies itself as “Byzantine chant” but is, by any definition, the equivalent of the Kraft pastitsio recipe:

That’s from the pen of yours truly, written about ten years ago (do note that I do not credit a composer in the score, partially because even then I knew enough to know that I didn’t want to be blamed later). I cringe to show it to anybody because there is so much that it gets wrong, but in the spirit of being the chief of sinners, I’d rather hold up my own mistakes than point fingers at those of other people.

First, it’s the wrong mode. Yes, fine, fourth mode is the mode appointed for this apolytikion, but this is the wrong version of fourth mode — it is diatonic (legetos) rather than soft chromatic, because apolytikia in fourth mode use soft chromatic.

The second and third things wrong are related — this text actually is supposed to be metered for a model melody, usually known in English as “Be quick to anticipate”, which the melody I wrote doesn’t follow; alas, the text is not in fact metered, and the service book from which I got this translation doesn’t include a rubric for a model melody. You don’t know what you don’t know.

Fourth, if you look at the model melody (Byz notation version in English here, staff notation here, or get them from 27 September here if those links don’t work) it really is one note per syllable for the vast majority of the hymn. What I wrote isn’t obnoxiously melismatic, but neither is it sufficiently consistent in being syllabic.

Fifth, it’s not a terribly sensitive setting of the text. I have no idea what I was thinking on “our God”, for example.

Sixth, the use of drone is all over the place. It’s clear that this is by someone who has no idea what they’re doing on this point.

Seventh, my use of the theses bears basically no resemblance to the reality of how classical scores use them, and since at that point I was almost entirely influenced by Kazan, it is probably is more Sakellarides-esque (if we can even aim that high) than anything. You can sort of see what I thought I was doing, but I may as well be using yogurt instead of Béchamel.

Eighth, I made a deliberate choice to eliminate measures, partially because I felt that the “tyranny of the bar line” actually made Kazan much harder to use. This wound up obscuring the rhythmic structure that the piece should have had, and it had the technical effect, due to how Sibelius works, of obscuring how the accidentals function.

Ninth, because I was just writing note to note in staff notation, with no understanding of how the rhetoric of the theses was constructed in psaltic notation, it’s made an even lesser effort than it otherwise was. If I had had even some knowledge of the notation and the orthography, a few of the problems could have been minimized a bit.

In all of this, I was doing the best I could with what I knew, and I was doing so with foundational materials that were less than ideal but were what was available to me, to be sure, but that’s just the point — by way of comparison, I had had a taste of pastitsio at a Greek festival and thought, hey, I’m a good enough cook that I can replicate that — and I came up with a random combination of pasta, meat, cheese, and yogurt based on ingredients I had on hand. Yes, sometimes one makes stew with what one has (you knew I’d get back to that eventually), and one might argue that it’s not that bad on its on merits (if one were being maximally charitable), but you can’t really call it pastitsio, at least with no disclaimers or scare quotes.

Thankfully, these days there are more resources that allow one to go a route that is more along the lines of Michael Psilakis, taking apart the tradition and putting it back together for an Anglophone Orthodox audience that perhaps has decent musical sense but needs detailed help for Byzantine music. What is still needed is greater access to teachers who can provide enough of a living connection to the material, such that that one can manage with a more bare-bones set of resources, like the basic pastitsio recipe, but we’re getting there. In taking advantage of such resources, ideally we would produce a body of Anglophone repertoire that is both composed and sung knowledgeably and faithfully, and as a result, Byzantine chant would eventually become something that is no longer perceived as “Greek” or “Arab” or foreign in general, but simply “what we sing”.

We can apply this, really, to any Orthodox musical idiom, and even any element of Orthodox tradition; a confused jumble of ingredients put together out of a lack of understanding doesn’t actually cultivate a real “American” expression of anything. It’s exactly that — a confused jumble of ingredients. We’re far better off putting in the time and the humility to learn from people who know what they’re doing and have a living connection to the tradition. Yes, it will take longer, yes, it may take trying some things that don’t work the first time, yes, you may have to un-learn and re-learn some things.

Be that as it may — certainly, in the case of pastitsio, the end result tastes a heck of a lot better.

We really need to get (real chanted) sound examples of the entire English Anastasimatarion, for starters, from St. Anthony’s Divine Music Project.

If appealing to my enjoyment to pastitsio wasn’t enough…well done!

Ultimately, many of your points are to the side of the thrust of this piece, which was to address the seemingly widespread perception that it doesn t work for choirs in fact, it *is* music for choirs. Even so, what you say is absolutely worth responding to, so here are my thoughts. First off, so that you have a general idea of where I m coming from, you might find this essay intriguing: Pastitsio and Byzantine chant: in which one finds, at the very least, the best pastitsio recipe ever (also the worst) (LINK)

Hi there! Regarding the choral point, a couple of months I published a piece very specifically about that a couple of months ago in Orthodox Arts Journal: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/byzantine-music-is-choral-music/