Organizing an event is a heck of a lot of work.

I had originally contacted John Boyer in late fall of 2008; I was looking around for Western notation transcriptions of Byzantine chant in Greek, and my friend Mark Powell said he was the guy with whom to inquire, and that I might also be interested in the curriculum he was developing for Byzantine notation. John was more than generous in providing very useful materials, and I figured, while I was corresponding with him and he was seeming friendly, I may as well ask what it would take to get him out to Bloomington for a workshop. This had been an idea I’d been trying to develop for a couple of years, since we were encouraged at PSALM in 2006 to try to put together local and regional events, but I’d never gotten more than a lukewarm response — “Who?” “Isn’t he too far away and too expensive?” etc. I figured it couldn’t hurt to ask him while I had his attention, however, so I did.

He quoted me a much more reasonable number than I was anticipating. I told him, right, let me check on a couple of things; I was able to convince a private donor to pay John’s fee and travel, Fr. Peter had no problem with it (particularly since it wasn’t being paid for by the parish), and I wrote back and said, let’s do it.

Well, then it took a year to make it work with everybody’s schedules. We decided on this last weekend back in August, and what I will say is that given a host of factors (not the least of which was the decision, made a month later, to bring out Andrew Gould the weekend before John’s visit) I would not have wanted any less time to get everything together. Even with five months’ advance planning, a significant chunk of my choir still couldn’t make the weekend work (although, in all fairness, one of them, Megan’s goddaughter Erin, was busy winning the Met auditions, so I guess that’s an acceptable excuse).

In October, the money from West European Studies happened; this really expanded the scope of what I had originally considered from maybe my choir and a couple of other interested parties to something that could be (well, had to be, given WEST’s terms) open to the public and conceived of as an educational outreach event. John and I finalized the schedule and the repertoire on 23 December; the Friday evening session would be the “lecture” of the series, intended to function as the academic side of the weekend, and then Saturday would be the all-day practical part. I set up a Facebook event and sent out press kits to 30 different churches, chairs, institute directors, community choral ensembles, and local news organs the first week of January, and was astounded at the responses that started rolling in. I heard from School of Music faculty; both an Early Music Institute and a Choral Conducting professor registered, and it came back to me that the Choral faculty member was even telling her entire doctoral seminar to come. I heard from a faculty member at University of Louisville presently teaching a seminar on early notation (although she ultimately decided she couldn’t make it); I heard from choir directors and priests in Indianapolis, Evansville, and Louisville; I heard from a Medieval Studies professor at Wabash College; I heard from local people in the community. By the time the registration deadline passed the week before, 45 people were registered; another ten confirmed over the course of the following week, and then still more showed up unannounced.

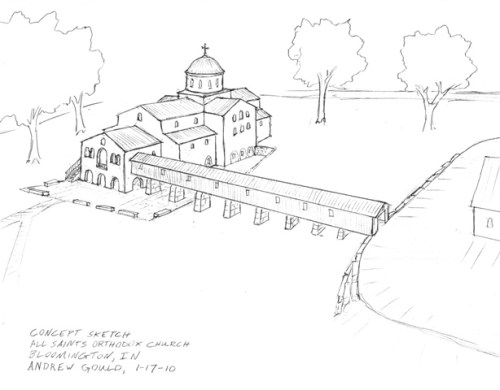

The last week before the workshop, the event planning was approaching a fulltime job; I had to make sure food got ordered and picked up, I had to track down CD shipments so we could have things to sell over the course of the weekend, I had to bug overworked Cappella Romana executive directors for scores (sorry to have been a nag, Mark, truly), I had to get registration materials printed and assembled, and I had to field phone calls from people who wanted to come but lived a couple of hours away and wanted to make sure it would really be worth their time. The last couple of days I wasn’t quite a one-man army; Megan, God bless her, helped with a lot of the last-minute errands and the putting together of the registration binders. I put together a couple of displays of Andrew’s concept sketch (pictured) so that workshop attendees could see it, at least trying to give a nod to the non-singer-friendliness of our space and indicating that we intend to do something about it.

The last week before the workshop, the event planning was approaching a fulltime job; I had to make sure food got ordered and picked up, I had to track down CD shipments so we could have things to sell over the course of the weekend, I had to bug overworked Cappella Romana executive directors for scores (sorry to have been a nag, Mark, truly), I had to get registration materials printed and assembled, and I had to field phone calls from people who wanted to come but lived a couple of hours away and wanted to make sure it would really be worth their time. The last couple of days I wasn’t quite a one-man army; Megan, God bless her, helped with a lot of the last-minute errands and the putting together of the registration binders. I put together a couple of displays of Andrew’s concept sketch (pictured) so that workshop attendees could see it, at least trying to give a nod to the non-singer-friendliness of our space and indicating that we intend to do something about it.

On the other hand, once John actually got here, my job was significantly easier — I pretty much just got to sit back and enjoy the proceedings.

I must say it was worth it; all in all, throughout the course of the weekend, about 65 different people came. Not bad for an event centered around this obscure, gaudy Eastern repertoire that supposedly we Westerners can’t stand without the edges sanded down.

I picked John up at the airport last Thursday evening; his flight arrived at 10:30, and then between his checked luggage taking forever and my very smooth wrong turn leaving the airport, we didn’t get back to Bloomington until about midnight. Luckily, Megan had a wonderful meal and a good bottle of wine waiting for us when we got home (a Saveur recipe that turns lentils and sausages into a bowl of gold), and we three were up talking until around 2 in the morning.

In what would prove to be a pattern for the weekend, four hours later, it was necessary to be up and about. It was, as I told John, the “showpony” day; he was doing a radio interview for Harmonia in the morning (watch this space for details), a mini-lecture for WEST in the afternoon (no thanks to me; I had both the time and the place wrong, forcing us to rearrange our afternoon a bit), a coaching with Lucas, Megan and me on epistle cantillation, and then the first formal session of the workshop in the evening.

One thing that putting on such an event at All Saints did was push us to the absolute limits of what we’re able to do in our current space. John had a PowerPoint slide deck as part of his lecture; well, we’re a pretty low-tech parish on the whole, so I had to go out and hunt down a projector and a screen. WEST loaned us the projector by way of the Russian and East European Studies Institute; my old employers, the Archives of Traditional Music, were good enough to loan us the screen. Even so, it was difficult to figure out how to set up the presentation in our nave to maximize the size of the slides, minimize keystoning, and be within reach of our power outlets (even with extension cords). We managed, but I’d want to figure out how to do better next time.

We had made the decision to install a comprehensive sound system in the nave as the only real cost-effective solution to our acoustic woes for the time being; we gave the thumbs up to the order on 11 January, and the guys at Stansifer Radio turned it around as quickly as the possibly could, knowing that we hoped to be using it by 22 January, and they got it installed by Vespers on Wednesday, 20 January. John had also wanted to be able to plug his laptop into the sound system; I told Greg at Stansifer what I needed to do, and he told me, “Give me an hour to make you a cable.” An hour and twenty dollars later, I had exactly what I needed, and it worked beautifully.

In the end, where we needed to set up John’s presentation was nowhere near the condenser microphone installed for the homilist, so we still had to give him a handheld mic hooked up to Fr. Peter’s old amplifier so he wouldn’t kill his voice. (Why, you might ask, did we not plug the handheld into the nice sound system? Well, the mixer is back in a closet in the sanctuary, roughly 30 feet away from where John was standing. We had a long enough cable, but plugging it into the mixer produced no result. “Oh, right,” Fr. Peter said, stroking his chin. “I forgot — the long cable is dead.” Like I said — we’re kind of a low-tech community. Note to self: replace long cable before next such event.)

Nonetheless, John was a hit, a big one, and something that I heard from more than one person at the end of the session was, “You know, I was only going to come for tonight, but I need to rearrange my day tomorrow so I can come here.”

Following the lecture session, in lieu of a formal reception (which I’ll have to remember to set up for next time), a number of us tried to go to Finch’s for dinner, it being one of the nicer places in Bloomington. Alas, we got there just as the kitchen was closing, and so we relocated to Nick’s. It was a bit louder than we we might have liked otherwise, and they didn’t quite know how to make a Manhattan properly, but perhaps not an inappropriate venue, given that it was founded by a certain Νικόλαος Χρυσόμαλλος (Nick Hrisomalos).

It was a full house at Chez Barrett; besides John, our friend Max Murphy, my counterpart at Ss. Constantine and Elena in Indianapolis, was staying on our other futon for the night so that he wouldn’t have to commute. Once again, we found ourselves up until about two in the morning chatting, and needing to be up by about 6:30 to make sure our houseguests would be sufficiently plied with coffee and eggs, pick up the food for Saturday’s lunch (shout out to Eastland Plaza Jimmy John’s; three 30-piece party platters was a perfect amount of food for a very reasonable price, and they were gracious enough to have somebody there at 8:30am so I could pick it up, since All Saints is waaaaay far out of their delivery area), and get everything at the church set so that the 9am session could start on time.

Well, it didn’t quite. We might say that everybody was inspired enough by the previous evening to recalibrate their clocks to “Greek time,” and we didn’t get started until about 9:30am. Έτσι είναι η ζωή (that’s Greek for c’est la vie, which is itself French for “Life sucks, get a helmet”).

Without giving a blow-by-blow of the whole day, I’ll say that much of the day was dedicated to rehearsing the Divine Liturgy music, but there were a couple of theoretical points made that I’ll note. First, there was the issue of time, which John got at a few different ways. He has a principle, stated many times over the course of the weekend, that “If you think you’re not going fast enough, slow down.” Too often, he says, we just zip through the text like it doesn’t mean anything, which makes it not mean anything. This can be in chanting a hymn, reading the epistle, whatever. We treat hymns and readings like they’re just the next thing to get through so we can be that much closer to getting out the door, rather than adorning them with the beauty that a) they deserve and b) will make us want to be there and take part in the services as though they are gifts from God rather than as burdens to bear. So, again — if you think you’re not going fast enough, slow down.

Without giving a blow-by-blow of the whole day, I’ll say that much of the day was dedicated to rehearsing the Divine Liturgy music, but there were a couple of theoretical points made that I’ll note. First, there was the issue of time, which John got at a few different ways. He has a principle, stated many times over the course of the weekend, that “If you think you’re not going fast enough, slow down.” Too often, he says, we just zip through the text like it doesn’t mean anything, which makes it not mean anything. This can be in chanting a hymn, reading the epistle, whatever. We treat hymns and readings like they’re just the next thing to get through so we can be that much closer to getting out the door, rather than adorning them with the beauty that a) they deserve and b) will make us want to be there and take part in the services as though they are gifts from God rather than as burdens to bear. So, again — if you think you’re not going fast enough, slow down.

Another way he stated this was to discuss the difference between χρόνος (chronos) and καιρός (kairos). The former is the world’s time; the latter is the Church’s time. This came up when he was talking about why some hymns are slow and melismatic, and even sometimes will revert to nonsense syllables — in the case of the latter, when this happens, the text has been stated thoroughly in a slow and melismatic fashion, and the hymn is now using “terirem” or some such to provide the opportunity to meditate on the text. Not only that, however; the whole point of the slow, melismatic style has a practical component — to cover a liturgical action, for example — but it also emphasizes the reality that in the liturgy, we are no longer in the world’s time (chronos) but on God’s time (kairos). I was reminded of what Met. Kallistos Ware says about the first time he was in an Orthodox church:

…I had no idea how long I had been inside. It might have been only twenty minutes, it might have been two hours; I could not say. I had been existing on a level at which clock-time was unimportant” (“Strange Yet Familiar: My Journey to the Orthodox Church” in The Inner Kingdom, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000, p. 2).

As he acknowledges in the same essay, this itself was a trope (albeit realized after the fact) of what the Kievan emissaries are reported to have said after their visit to Hagia Sophia: “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth…”

Another thought came to mind during this discussion — what do we sing in the Cherubic Hymn? “Let us now lay aside all earthly cares.” What do most of us do with the Cherubic Hymn in our parishes? Sing a setting short and fast enough so that we repeat it three times, because we worry that people will get bored otherwise. Isn’t that rather missing the point?

The other theoretical point John made was that there are three textures of singing in our liturgical practice: soloist (priest or deacon or cantor, depending on what’s happening), choir, and congregation. “We need all three,” he said repeatedly. “It’s very much a dance of who sings what when, and if you limit yourself to only one of those textures, you lose something important and beautiful.” As you may recall, the week before, somebody told Andrew Gould that they didn’t come to church for the beauty but for the participation; one wonders how such a perspective would understand what John had to say on this point. My thought is that he’s right, but dances have to be both taught and learned or they become mass confusion.

The services themselves were an adventure, but a good one; at the kliros, the weekend suddenly turned into Byz Chant Boot Camp (or Parents’ Weekend of same, as our friend Laura Willms suggested), and John was the drill sergeant. This Was A Good Thing; he was able to do get away with making certain points in a way I simply can’t, partially because a) he won’t have to see these people next weekend b) we paid him to be here specifically to do that c) he’s Greek. He was not shy about being emphatic in terms of instructing people during services; if you were on the isokratima, for example, and were sleeping on the job and missed his cue for the move, you got an elbow in the ribs. (As John said later, and I absolutely agree with him, “Please tell me a better way to communicate with people who aren’t watching me while I am singing.”) The thing is, coming from him, people ate it up; after the service, a lot of the folks who got the business end of his drill sergeant-ness said only, “Wow — what an amazing teacher.” For me, how this manifested was him pointing to the Byzantine scores he was following and saying, “You’re reading with me, got it?” Up to that point, I hadn’t dared putting enough confidence into what I had learned over the summer to actually use it during services, but much to my own surprise, I managed to keep up. I wasn’t perfect (and when it was just me on my own I fell down and went boom a couple of times), but I kept up.

After Vespers, we were all tired and hungry enough that it seemed best to simply call off the 7-9 session — we had reached enough of a logical stopping point that anything further that evening would be a matter of diminishing returns. It was early enough that Megan, Laura and I were able to take John to Finch’s for dinner after all, and once again we all found ourselves up until 1am or so talking.

Matins and Divine Liturgy the next morning were not without their speed bumps — everybody was just enough out of their element to make sure of that — but everything went quite well regardless. (We even made it successfully through the Cherubic Hymn, which had been a cause of some lack of sleep on my part.) A lot of non-Orthodox workshop attendees came, so we had a very full church. That said, I’m not entirely certain that everybody in the parish knew what was going on or why we were doing what we were doing (despite my plugs for the weekend along the way), and some of the reactions I got from parishioners were worded accordingly (“That was beautiful, Richard, but I will be very happy when we go back to normal” was one example). On the other hand, there was the chorister who told me, “I felt like my musical soul had been fed for the first time in a long time.”

Here’s a comment made by a workshop attendee to which I keep returning — the commenter in question is part of the local UUC congregation and retired English faculty here at IU:

Excellent workshop on Byzantine chant this weekend at All Saints Orthodox church in Bloomington, with John Michael Boyer, cantor and teacher… The whole attitude of the Orthodox faith tradition is very flexible, welcoming, inclusive, and constantly changing–such a welcome change from most of the Western Christian churches… As it happens, I’m not a theist of any variety, but if I were monotheistically inclined, I’d give this church a serious thought. Good people all around… This was my third visit to your church and in every case, I was much welcomed.

Seems to me that’s successful outreach right there.

John’s flight out was scheduled for 4pm on Sunday. However, as we left All Saints around 12:30pm, he looked at me with deeply exhausted eyes and said, “Would you mind horribly if I changed my ticket and stayed an extra day?”

Well, I told him, I didn’t know for certain where he’d stay, but I’d see what I could do.

Megan and Laura made biscuits and gravy, which I think may have cemented John’s friendship with Bloomington (to say nothing of his arteries). He got a nap, and made a wonderful dinner for us that night — a recipe of his own devising, incorporating pasta, kielbasa, kalamata olives, mushrooms, and green peppers.

(Tellin’ ya — how do we rate all of these friends who ask, “Hey, can I cook in your kitchen while I’m here?”)

And, once again, we looked at the clock while talking, found that the hours had slipped away and it was three in the morning.

On the way out of town the next morning, we had lunch with Vicki Pappas, the chair of the National Forum of Greek Orthodox Church Musicians — also a Bloomington resident and founding member of All Saints (alas, in absentia for years, since she commutes to Holy Trinity in Indy). It was a very interesting conversation for which to be a fly on the wall; the musical situation in GOArch has its own intricacies, complications, and vicissitudes, to say the least.

The drive to the airport (no wrong turns this time, thank God) mostly consisted of us discussing how to get John back here, and soon. Watch this space.

Just to make sure I’ve said it: as with Andrew, I wholeheartedly recommend John if you’re looking for somebody to bring out as a speaker or as a guest instructor with respect to Byzantine chant. He’s knows his stuff inside and out, both in terms of chant and in terms of liturgics in general, he’s a great teacher, and of course he’s a wonderful cantor. He is a very effective speaker and teacher for an academic audience, an Orthodox audience, and a general audience — not something everybody can claim.

All in all, the weekend was a huge success in terms of being outreach, being educational, being of musical interest, and, more personally, building friendships. It’s very true that there’s very little in the way of specifics you can cover in a weekend; notation wasn’t discussed beyond some theoretical ideas, and there was only so much he had time to do with respect to the tuning systems, but I think what it did was threefold: it established that there is in fact interest in this material here in Bloomington, for the School of Music, the greater community, and the parish, it proved that you could talk about this subject from an explicitly confessional standpoint and have it be more informative for non-Orthodox participants than it would have been otherwise, and it stimulated interest in doing more. The School of Music faculty who came were very clear about wanting to participate more directly the next time John is here; people from the parishes of surrounding areas said, “Hey, how can we help with the next one?” and it’s also been expressed to me that there is a desire to figure out what portions of what we did last weekend we can keep as our normal practice. That will likely be a complicated conversation with a complicated outcome, but it’s a better response from the people in question than “That was nice, now let’s never do it again”.

What I will say is this: by virtue of the fact that we were open to the public and not charging admission, our own success made it quite a bit more expensive than we had originally planned. If you participated and would like to help, or would like to help regardless, please contact me (rrbarret [AT] indiana.edu). Our original donor has been very generous, but we had hoped to come away from this event with perhaps some seed money for the next one as well. Looking ahead, I am contemplating starting something which we might call “Friends of Music at All Saints” or some such, specifically to exist as some kind of a booster organization for such things; again, I am pretty much a one-man army here, so if you’re interested in participating, please let me know.

So, we had two visitors two weekends in a row. One told us about beautiful churches, another told us about what we do in those beautiful churches. Now what?

I think, if we want a useful synthesis of Andrew’s and John’s respective messages, it boils down to John’s point about kairos and chronos, and how that relates to the church building being an icon of the Kingdom. As Lucas pointed out to me, the word kairos kicks off the whole Divine Liturgy: Καιρός τοῦ ποιῆσαι τῷ Κυρίῳ — it is the time/moment/opportunity of acting for the Lord. Even better, if we want to read τῷ Κυρίῳ as a dative of the possessor, it is the Lord’s time of action. And what is the priest’s first blessing? Blessed is the Kingdom… The Liturgy is the Lord’s action in His own house on His own time. (I will note that this does not go well with the populist misunderstanding of “liturgy” as “the work of the people”, but it goes much better with the more accurate rendering of it as “public service”. It is the Lord’s public service being offered to His people, in other words.)

So, you have to liturgize in a way that emphasizes the fact that it’s God’s time, and you have to have a worship environment that emphasize’s that it’s God’s house. As Lucas also put it, you have to get across the idea that, no, actually, you don’t have anyplace better to be.

Schmemann, of course, talked about the idea that we should liturgize in a way that takes the Liturgy back out into the world. What I wonder is if we have a problem with the valve running the wrong way — that we bring our busy lives, our distractions, that is to say the world into the Liturgy with us and then expect the Liturgy to be run in a way that accommodates us. As I said with the Cherubic Hymn — we say that we are now laying aside all earthly cares, but do we really approach that text in a way that indicates we believe that that’s what we’re doing?

And when you’ve got a building that, no matter how you cut it, looks like an office building with icons and which traps our psalmody rather than lifting it up to heaven, is it any wonder that that’s our approach? Andrew was absolutely right — we’ve got the saints and the angels, but no City.

We’ve got our work cut out for us. On the other hand, here’s the good news — Fr. Peter told me a couple of days ago, “You know, a comment I got from a few people was that things seemed too slow. But you know what? In a lot of places, by having the choir sing it so slowly, I found that it matched better with the liturgical action, and it made a heck of a lot more sense.” We talked about a lot of this stuff, and it seemed to click with him that we need to figure out, and make a concerted effort reinforcing, the difference between kairos and chronos. It’s not going to be easy, but we’re at a point where it’s what we have to do.

The project that All Saints has ahead of it is not a building project or a musical project. Those are components, yes, but what it really is is a spiritual project. We’ve got to be the City on the Hill, the Heavenly City, the New Jerusalem, the Light that is not hid under a bushel. It is desperately needed in this town, in this area, in this world, and we’ve got to convince ourselves that we want to be that, that we want to be an icon of the Kingdom, more than we want to be what we’ve been pretty good at being up until now, which is a little, struggling church in a little, struggling Midwestern town.

If we can do that, then we will have the hard part out of the way. If we can convince ourselves that we believe that and that we can walk in faith, then the temple will just about build itself, $2.5 million or no, and people will stop worrying about whether or not the music is too Byzantine or too slow or not congregational enough or not “American” enough or whatever. (By the way, I found over the course of the weekend that just joining a good English translation with a melody written for the English made things pretty well more “American” on their own. Others may disagree with me, but that was my perception.) If there’s a point that both Andrew and John made, it is that the ethos of the received tradition is not a buffet, not a “meat and three”, not a list of things from which you pick and choose. There are things that we can adapt for local circumstances, but you do that after you’ve received the tradition, and then only in a way that doesn’t obscure what you’ve received. You don’t filter out the parts of the received tradition you don’t like pre-emptively. You may well come to church for participation rather than beauty, but that doesn’t mean that beauty isn’t part of the organic whole.

The church building and the liturgy have to reflect the fact that we worship a God who is bigger than we are. God already “met us where we’re at” in the Incarnation; it is up to us to respond to that in faith.

Now, having said all of that, I’m at the head of the line of people who need to figure out chronos and kairos. With these two weekends out of the way, I have a ton of reading to do on Ancient Greek democracy and a couple of weeks’ worth of working out on which I need to catch up. I’m going to be juggling things for a bit yet before I’m really into the rhythm of the semester. Along similar lines, last Wednesday, John texted me at about 8pm my time: “I’ve turned nocturnal. Just woke up. I’m not sure, but I think it’s Bloomington’s fault. :-)” I guess the gap between chronos and kairos gets us all in the end. Pray for us.

More importantly, however, pray for All Saints. We’ve got a lot of hard work ahead of us. With God’s help and by your prayers, we can do it. If you want to be involved more substantially, I’ve suggested a couple of ways you might be able to do so; contact me if you want more information.

Okay — back to being a student.

This has been in the works for a little over a year, but the time approaches quickly and with the new semester upon us, I am kicking the publicity into high gear (at least as high as I can working on my own).

This has been in the works for a little over a year, but the time approaches quickly and with the new semester upon us, I am kicking the publicity into high gear (at least as high as I can working on my own). From yesterday’s Synaxarion reading:

From yesterday’s Synaxarion reading: My copies of

My copies of  Now, what does any of this have to do with Ensemble Organum’s recording? Hang on for a second and I’ll explain.

Now, what does any of this have to do with Ensemble Organum’s recording? Hang on for a second and I’ll explain.