Read my re-post of Fr. John Peck’s “The Orthodox Church of Tomorrow” first, and possibly Anna Pougas’ post on American Orthodoxy as background if you haven’t already.

When I was in New York for the Fellowship of Ss. Alban and Sergius conference, my friends Peter and Soula called me, saying they just wanted to let me know I was hanging out with them before I headed home. The way this was going to be best effected was for me to spend Sunday morning with them, and they were good enough to pick me up at St. Vlad’s and take me out to Ss. Constantine and Helen Orthodox Church, a Greek parish in West Nyack, New York. Oh, by the way, they told me as we walked in, you’re helping with Orthros.

The priest, Fr. Nicholas Samaras, arrived. He gave me a blessing and asked where I was from. “Bloomington, Indiana,” I replied. He sized me up a bit and said, “Ah. Sounds like a good place to be from.”

Orthros/Matins wasn’t a problem; Mr. Michaels, their psaltis, would sing a verse of something in Greek, I’d sing a verse of something in English (occasionally in Greek if I knew it well enough), then Peter would alternate between Greek and English, and Soula read the psalms and prayers. It was a wonderful church in which to sing; it’s a big building with a high ceiling, and you don’t feel like you have to push at all to be heard (unlike what I’m used to, alas).

The Divine Liturgy was sung by a choir rather than the psaltai (ευχαριστώ πολυ Στέφανε αλλά τώρα είμαι συγκεχυμένος — είναι οι ψάλτες ή οι ψάλται;), but Peter and I alternated on verses for the antiphons with the choir singing the refrains. It was also mentioned to me, “Usually somebody chants the Epistle in Greek and somebody else reads it in English, but the guy who chants it isn’t here — do you want to chant it in English?” And so I did. (I purposefully don’t travel with my reader’s cassock, but this was a morning where I wished I’d had it.)

After the Liturgy, I went through the line to venerate the priest’s cross and get a blessing. Fr. Samaras blessed me and said, “Um… don’t move. Just… just don’t go anywhere for a moment.” Uh oh, I thought. I stepped on some toes and I’m going to hear about manners when one is a guest. When all had been blessed, he turned to me and said, “What time do you have?”

I looked at my watch. “Quarter after twelve.”

“Ah, okay. And how long will it take to move you and your wife out here?”

Following that, there were a couple of very kind older gentlemen who thumped me on the chest and told me, “Young man, you’ve got a gift from God.” Peter’s parents (who I had just met for the first time a week and a half earlier when they had visited Bloomingon) referred to me as “family”. Fr. Samaras was very serious about wanting to keep in touch, and we’ve kept up a correspondence since. Don’t tell me that Greeks (to say nothing of New Yorkers!) aren’t welcoming; I don’t want to hear it. I’ve also found Holy Assumption Church in Scottsdale, AZ to be very welcoming with a terrific priest, as well as Holy Apostles in Shoreline, WA (where I attended my very first Divine Liturgy). The blanket assumption that “Greeks would prefer non-Greeks to stay away” is categorically false; let’s make that clear.

I also think that the convert or the inquirer who finds himself/herself in a community with a strong ethnic contingent needs to see such a situation as a gift from God, and to approach such a parish community with a dollop of humility roughly the same size as the dollop of sour cream which I put on my nachos. The “ethnic enclave” temptation faces the convert every bit as much as anybody else — you get a community of converts who read some Lossky, Schmemann, Hopko, etc. when they were still Episcopalians a couple of years ago, and there’s a danger of an exclusivist mindset developing, very similar to what the Greeks (or the Russians, or the Romanians, or whomever) get accused of having. Reading everything in a book doesn’t make you Orthodox; you can’t teach yourself to be Orthodox, period (thank you, Seraphim Danckaert, for sharing those words of wisdom oh so long ago; they’ve stuck with me). Whenever a convert/inquirer complains about the icons looking too weird or the music sounding too strange or the language being wrong (I know of one guy for whom liturgical English isn’t close enough to “the language of the people”, let alone Greek, Slavonic, or what have you), my first thought is simply, “You’re not ready yet.” There are some things you don’t like which you have to accept with humility, however good your reasons for not liking them seem to you at the time. Icons, incense, chant, vestments… and, yes, depending on where you wind up, pews, organs, people talking during Holy Communion, and liturgical schedules that are Sunday-only. Regardless, the aforementioned gift from God is the chance to learn the faith from people who have lived it for generations, however imperfectly, rather than building up a Platonic ideal in your head from books up to which no actual parish in the world can ever hope to measure. Learning the Orthodox Christian faith from somebody’s grandmother, believe it or not, is going to actually teach a person a lot more about what it means to live the life than reading Schmemann, even if it means having to move out to aisles to prostrate during the Prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian because pews get in the way otherwise. (And I say that as somebody who thinks you can never read enough Schmemann.) To the people who claim that we need an idiomatically and uniquely “American” cultural expression of Orthodox Christianity and we need it yesterday, I say: chill, guys. Receive the Tradition. Let it change you and yours for a couple of generations (at least) before deciding it needs updating.

All that said, I recognize that not everybody can go to your typical Greek parish and just help sing Matins or chant the Epistle as nothing more than a visitor passing through, and not everybody has a chance (or the interest, or overall inclination or ability) to take a Greek class (ancient or modern), and not everybody knows people where they’re traveling who can be a conduit to other people in the parish. So, I don’t pretend my experience, which in general has been unique, is necessarily the general case. Let’s also not pretend that every experience in every parish in every jurisdiction I’ve ever visited has been positive; they have not. I also don’t wish to pretend that I’ve never visited a parish and turned my nose up at it because it didn’t meet my expectations or cater to me; I most certainly have, and five years later — to demonstrate God’s sense of humor — I’m still there, my wife and I were chrismated there, we’ve seen four godchildren received into the faith, I’m the choir director/psaltis, and I’m on the parish council. Those people are my family in every sense of the word. First impressions really can be meaningless.

Coming on the heels of the situation regarding Fr. John Peck’s article is wind I caught yesterday of how Sunday of Orthodoxy Vespers might work this coming winter. Holy Trinity, the big Greek parish in Indianapolis, wants to host; they’re just about to finish building the Indy regional campus of Hagia Sophia, and it will be, from a standpoint of both capacity and providing an exemplar of traditional Byzantine architecture, the ideal place to hold it.

There’s a catch, however — the choir made up of Orthodox singers from around the entire Indianapolis metro area (including Bloomington)? Gone. Part of the deal is, if you do it at Holy Trinity, you do everything in-house — their psaltai/psaltes (whichever it is — I’m confused now), their music, their organ (probably), end of story. That this runs entirely counter to the spirit of how the Indianapolis clergy have always tried to celebrate Sunday of Orthodoxy seems to be not an entirely relevant point. Okay, fine, that’s their right — but why suddenly take a hard line when it comes to playing with others?

To come back to Fr. John Peck, why come down so hard on a priest who, basically, is saying that those who identify with Orthodox Christianity on a basis of ethnicity and heritage are going to have to learn how to get along with those who identify on a basis of faith if they want the Church to survive in the United States? I don’t agree with everything Fr. John said; I think his view of the future is a little too rosy, but I think he’s got the point hands-down that the makeup of the clergy coming out of the next several class years of our seminaries is going to change some things, big time. What some want to hear or not, I nonetheless fail to see how what he says is hostile or out of line. It may not necessarily be what some people want to hear, but is it really that threatening for a priest to point out what is painfully obvious — that, as Fr. Seraphim Rose said thirty years ago, “ethnic Orthodoxy” is a dead end? The current generation, by and large, either isn’t learning the faith or aren’t learning to care about the faith — I know of priest’s kids at IU who, so far as I know, have never darkened the door of All Saints since maybe the first Sunday of classes their freshman year. My Greek class right now is three-quarters full of Greek American kids, some of whom, I’ve found, didn’t even know there was a church in Bloomington until I told them about it, and at whom I’ll be surprised (but pleasantly so) if they decide to come to a service. Now, let’s clarify — that’s not an “Orthodox problem,” but rather an “everybody problem”. Convincing kids they need church while they’re in college doesn’t work until they, well, realize they need church while they’re in college. But Greek/Russian/Serbian/Romanian/Albanian/whateverian families also need to realize that their kids aren’t necessarily picking up the faith of their forebears any better than their Anglo counterparts at Tenth United Methodist Church down the street — just because they have a language and a festival to associate with it doesn’t mean it sticks better. (Hats off to some very exceptional kids I know for whom it has stuck, and stuck very well. You know who you are and why I know you. You’re doing it right, guys.)

I wonder sometimes if part of the problem is money. By and large — that is, excluding Tom Hanks and maybe Chris Hillman (late of The Byrds and The Desert Rose Band), the converts coming into Orthodox Christianity are not wealthy people, at least based on what I’ve seen; we all do what we can, to be sure, but for example, my parish right now wouldn’t be able to build the janitor’s closet of Holy Trinity’s new building. We’re a community of mostly middle-to-lower class working folks as well as people from the university community, and we’re able to keep the lights on in our humble “temporary” space and pay our priest’s salary and benefits without much left over. That seems to be fairly representative of what I’ve seen in the parishes I’ve visited — converts keep the candle fund replenished, and the Greek and Lebanese doctors and lawyers, if there are any in the community to begin with, are the ones paying for the frescoing of the walls and the maintenance of the dome. Enough converts for a critical mass and the small, cradle-less community can at least be self-sustaining, but building even a simple, small traditional Byzantine church is going to be beyond the means of that kind of group. Could it be that for some “ethnic” Orthodox who actually do write substantial checks and whose grandfather may have helped to carve the iconostasis, they just don’t want to be told what to do and held in contempt by somebody who was a Baptist perhaps as recently as a year ago and whose offering might buy the incense for Holy Week? That’s perhaps ignoring the lesson of the widow’s mite, but I know from my own experience that the convert who’s given their two pennies can probably still pick up a broom or wash a dish, and not to put too fine a point on it, but that might even be what’s needed from them more than a discussion of how Byzantine chant is driving non-Greek inquirers away or the icons aren’t Byzantine- (or Russian-) looking enough.

One more thought, and then I think my bag of prolix dust is empty for the evening. There is a certain irony to me that the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, who in the early/mid-’80s suddenly wouldn’t give the Evangelical Orthodox the time of day (perhaps not for terrible reasons, depending on whose version of the story you’re hearing), has become a haven for certain former EOC communities who broke off from Antioch.

My hope is that Fr. John Peck comes out of this okay. What he had to say would ideally generate a conversation which needs to happen, and that isn’t anything over which he should be penalized. If he doesn’t, I hope he sticks to his guns — Antioch would probably take him with open arms (assuming a canonical release — Antioch is kinda touchy about such things). Pray for him, pray for the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, and pray that all Orthodox in America see something in Fr. John’s article, and the response it has received, from which they can learn.

I got some news on Friday that I’m thrilled to have received, to say the very least. It’s one part of a triple threat, a trifecta even, of excellent possibilities, and it is seeming rather possible right now that by this time next week, I will have found out that the other two, and thus all three, have occurred.

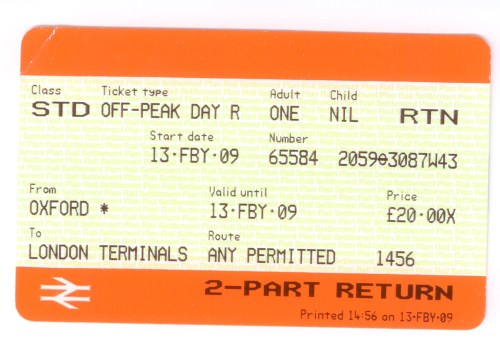

I got some news on Friday that I’m thrilled to have received, to say the very least. It’s one part of a triple threat, a trifecta even, of excellent possibilities, and it is seeming rather possible right now that by this time next week, I will have found out that the other two, and thus all three, have occurred. Thus, after refreshing ourselves with showers and fresh clothes, we took the Tube to Paddington Station from Charing Cross (this is a lot easier than it initially looks on the Tube map, by the way; you just push the waste all the way in so that the door can close… uh, wait — what I meant to say was, just take the Bakerloo line north from Charing Cross to Paddington — it looks like this shouldn’t work on the map, at least at first glance, but it in fact does), and off we went. An hour later we were getting off at Oxford station.

Thus, after refreshing ourselves with showers and fresh clothes, we took the Tube to Paddington Station from Charing Cross (this is a lot easier than it initially looks on the Tube map, by the way; you just push the waste all the way in so that the door can close… uh, wait — what I meant to say was, just take the Bakerloo line north from Charing Cross to Paddington — it looks like this shouldn’t work on the map, at least at first glance, but it in fact does), and off we went. An hour later we were getting off at Oxford station. I didn’t intend for it to take me over five months to translate the second half of this, but here we are. I have a nice long French article to read for a course this semester (70 pages or so, I think), so finishing this particular project seemed like a prudent refresher.

I didn’t intend for it to take me over five months to translate the second half of this, but here we are. I have a nice long French article to read for a course this semester (70 pages or so, I think), so finishing this particular project seemed like a prudent refresher.