(Warning: long and rambly. Sorry.)

This has been a difficult semester.

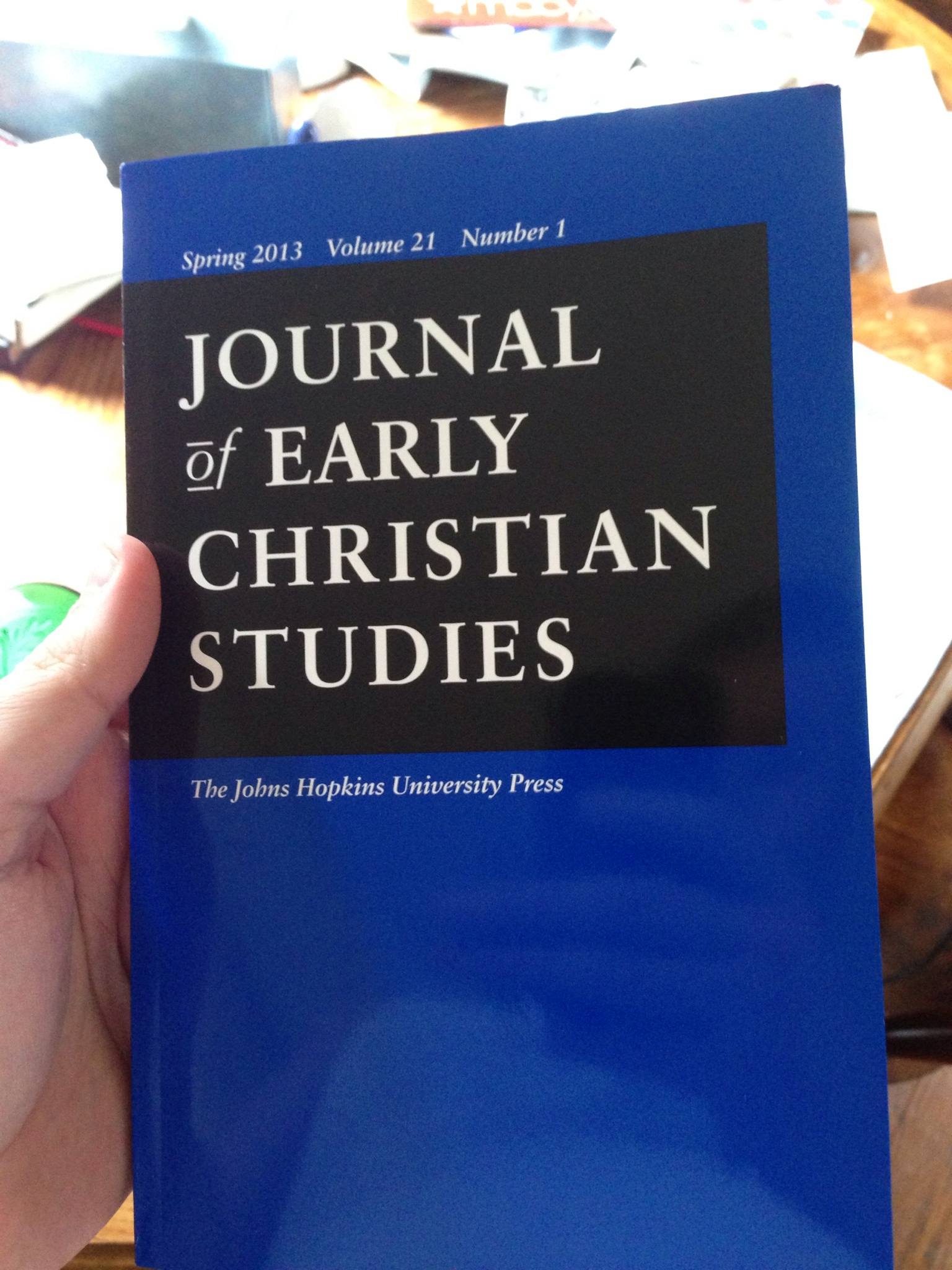

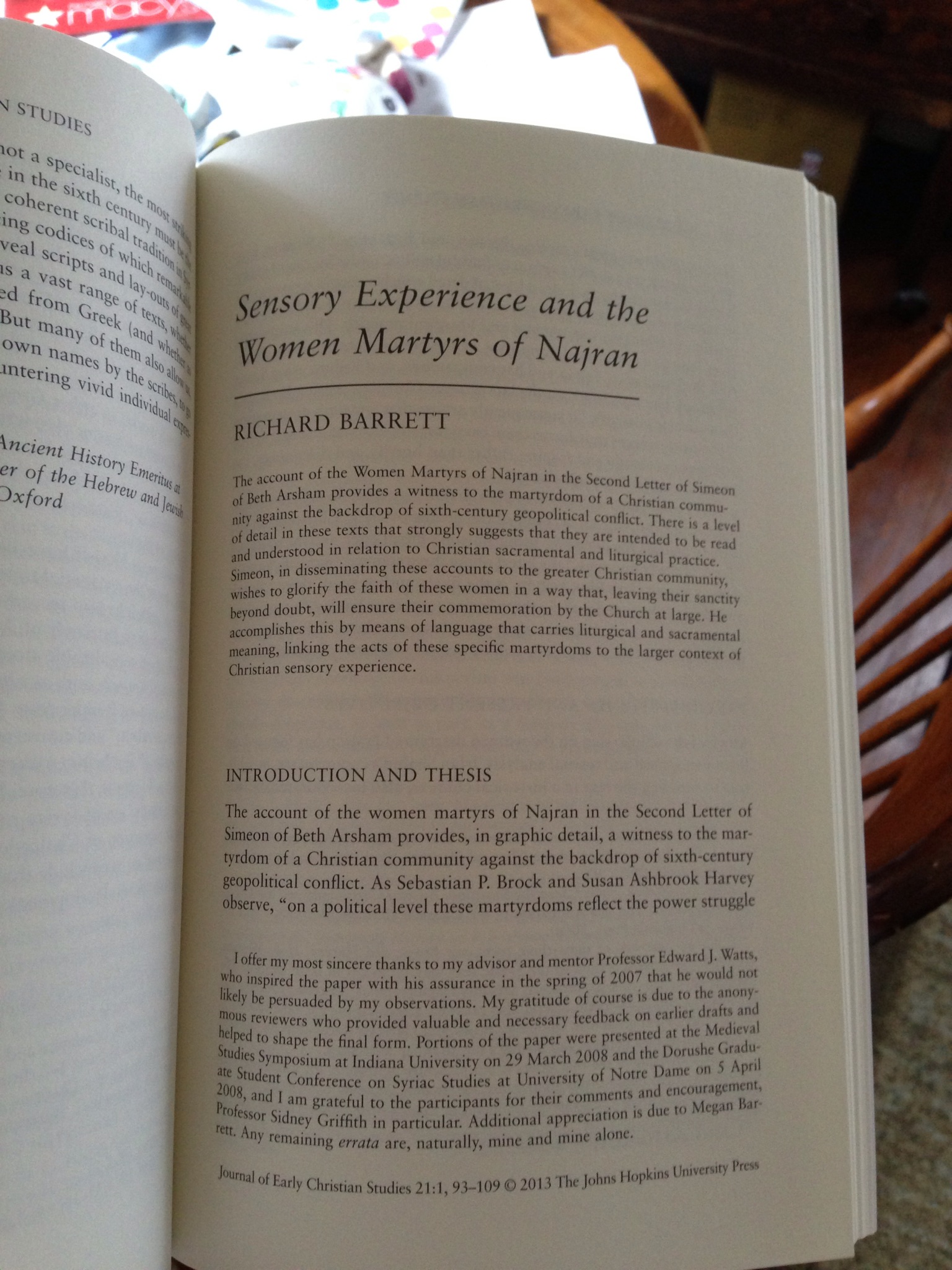

I’m at the point in my program where I’m having to jump over the big hurdles; this is no bad thing on the face of it, because I don’t want to be in grad school forever, I’d like to have a real job before I’m 40, and there are certain funding realities that mean it’s in my best interests to get to candidacy/ABD (“All But Dissertation”) sooner than later. To that end, this year has been all about getting myself through those hoops. Fall term I spent getting my Latin back in shape, I got that exam out of the way back in January, and now I’m three weeks out from my oral qualifying exams. Assuming all is well there, then I have a paper that I need to rework into a dissertation proposal, and then I can defend that before the end of April. Once I’m on the other side of all of that, then there are certain kinds of doors I can knock on. I don’t necessarily have to go knocking on them, since I still have two years of funding left and I’m pretty sure that if push comes to shove I can get the dissertation done in one year, but on the other hand, we’ve now been in Bloomington ten years, and we’re very much feeling like our own internal sell-by date has passed for this town. It would be very much to our advantage, on a few fronts, to be able to move on soon, and some of the research/teaching fellowship opportunities that are out there once both Barretts have unlocked the PhD candidacy achievement would be more than helpful in allowing us to move on.

See, we’ve basically been here long enough that we’ve outlasted just about everybody who moved here within our first two or three years. It’s one of the very weird things that can happen in this kind of town; you come here for one reason, thinking you’ll be in and out in two years, three years max, and then life takes a turn that keeps you here. It can be very subtle, really; it becomes clear that there’s really not a ton here that can keep you sufficiently busy if you’re not on one of a handful of very specific tracks, but somehow there’s a center of gravity here that can hold you in place even when you don’t really want it to. (A friend of mine calls this “getting Bloomingtoned”.) Part of it is that it’s logistically a difficult town to get in and out of; you can’t just hop a plane or train and be on your merry way. Part of it is that it can seem like there should be plenty to do here if you can just come up with the right opportunity; some of those opportunities only cycle through once a year, and by the time you realize that they’ve passed you by for the year it’s too late to make plans to do something someplace else, so you’re stuck until the window re-opens. Maybe you manage to make one of those opportunities work, and then the next thing you know, you’ve looked up and four years have passed. Eventually, one way or the other, stay here long enough, and not only will most of your friends have left, but the avenues that bring new arrivals into your social circle will re-orient around other people.

We’re feeling this right now particularly keenly, at least in part, because of Theodore. We just don’t have any access to family out here; my mom is in Alaska, Megan’s is in Washington state, my sisters are in Arizona and Oregon, and Megan’s brothers are in Hawaii, eastern Washington state, and Chicago. (Chicago seems like it shouldn’t be that bad, but it’s a lot harder than you might assume.) The plan this academic year was that theoretically our respective teaching/research schedules were going to allow for somebody to always be at home; well, that didn’t quite work out. Flesh of My Flesh got a last-minute (like, three weeks into the semester) teaching reassignment that threw a massive wrench into our schedules, and what we’ve realized is that just about everybody we would have asked for help in terms of watching the Fruit of My Loins for an hour here or an hour there has moved on. Every day has really turned into a juggling act, and it’s been hard to manage with basically not much local social network left.

One of the other things that’s contributed to feeling this diminution of our social circle is the fact that we’re no longer hooked in to the parish that is ostensibly local to Bloomington. (You perhaps notice that I’ve phrased that somewhat circuitously. That’s intentional, and I’ll come back to that.) Since January, we’ve been going to Holy Apostles Greek Orthodox Church in Indianapolis; it’s one of the shorter drives, they’ve been very nice and welcoming, they’ve fawned over Theodore, and they’ve been receptive of what I have to offer in the way of chanting. They also only meet twice a month, which means that we’re not missing out on much by commuting. But, even being one of the shorter drives, it’s still an hour and fifteen minutes away, and it means that our contact with the community is by necessity pretty sporadic. Anyway, the upshot of all of this is that a couple of weeks ago, when all three of us got really sick simultaneously, a friend of ours in Indianapolis who, like us, used to go to All Saints, asked us — “Is anybody checking in on you guys?” I just had to shrug and say, who’s left to do so?

Last week, I found out that a good friend of mine, whose time here has been very much the definition of “getting Bloomingtoned” (he and his wife moved here to be close to family and to apply for grad school; the family moved away shortly thereafter, grad school didn’t work out, and they kind of got snookered into staying indefinitely, under somewhat less than ideal employment conditions, for reasons I won’t deal with specifically) and who has been waiting for the opportunity to go to seminary for the last seven years, will finally be going to seminary this fall, come hell or high water. Last I had heard, while certain necessities had managed to fall into place in the last month, they had decided to wait until fall 2014; well, no, they’re getting the heck out of Dodge and they’re doing it now. They’re done feeling stuck here; time to take the opportunity to move on. Another couple of friends of ours are also moving in May, we’ve only recently found out, but they just arrived last May. The wife was starting a PhD program in education and the husband was doing some exploratory things for nursing, and, well, let’s just say that none of that really worked out as intended. They still thought that they’d stick around Bloomington for a few years simply to try to be rooted someplace for a little while, but as I found out, in the last few weeks they’ve seen that that way lies madness, and they’re moving back to their home state in a couple of months. They are, in other words, determined to avoid “getting Bloomingtoned”. I am happy for all of those folks. At the same time, much of our small handful of remaining friends here is also moving on to greener pastures come May, and we’re really starting to feel more alone than we have in awhile.

But my point here isn’t really to complain; my point is to give a personal window into the weird way this town works. To use theoretical terms, the way center and periphery function here is a bit tough to wrap one’s brain around. One way to look at it is that Indianapolis is a center, and Bloomington is on the periphery; some might argue that actually Chicago is the center, Indianapolis is part of Chicago’s periphery, and Bloomington amounts to the outer reaches of the solar system. Well, maybe; I tend to think that Indianapolis and Chicago are both centers; culturally, my impression is that northwestern Indiana seems to rely more on Chicago as a center, and central Indiana seems to rely more on Indianapolis as the center (which is to say, it feels a lot like a slightly rougher-around-the-edges version of Ohio). But then, Bloomington is, in its own way, also a center — Indiana University is here, for example, which makes it a particular kind of center. It’s not what anybody would call a “world class city”, but it neither tries to be nor wants to be, and there’s enough activity here for there to be surrounding areas that consider Bloomington to be “town”, which means that Bloomington has its own periphery.

The trouble with Bloomington being a center is that, even at a mere hour away from Indianapolis, it’s a pretty isolated center. It’s a short drive that feels long, partially because you don’t actually get to make it on a real highway; you’ve got a couple of choices of state highways that, instead of overpasses, have intersections and therefore stoplights, it also feels long partially because so there is so little between here and there. Its nature as an isolated center has let it become something of a SWPL paradise for people who can afford it; we’ve got a food co-op with three (soon to be four) locations, we’ve got a whole street of different kinds of ethnic restaurants (no real Greek restaurant, alas), we’ve got culture provided by the university, we’ve got all kinds of green initiatives, we’ve got birthing subculture, we’ve got a winery, we’ve got homebrewing galore, we’ve got alternative schools, we’ve got biking, and we sort of have buses. This has sort of led to Bloomington’s own kind of parochialism; the feds are supposed to build part of the I-69 corridor going through here, and the SWPL folks do not want it in any form at any price. Probably if there were a commuter train between here and Indianapolis, that’d be one thing (and I myself would love such an option, because I hate the drive), but on the whole, they like Bloomington the way it is.

Well, fair enough, but then there’s a whole separate crowd that lives here, one that lives more than 2-3 miles from the university campus, that actually doesn’t see the university as the economic center of the town; they see it, rather, as mostly irrelevant at best and an unwelcome attempt to co-opt the kind of life they had 15-20 years ago. “The university is actually only a small part of the picture,” a lifelong resident told me once, telling me that the only people who see IU as rooting the activity of Bloomington are people who work for IU. “Bloomington’s main economic driving force right now is retirement,” he said.

See, 15-20 years ago, Bloomington’s economy was far more diverse in general; there were the quarries, there was RCA, there was Otis Elevator — you had a substantial blue collar sector, in other words, that could co-exist, however uneasily (see the movie Breaking Away), with the eggheads, the retailers, and the burger-flippers. All of that’s gone now, for all intents and purposes; my first year here, I worked for Kinko’s FedEx Office for a few months, and my manager was a guy who had worked for years in management at RCA. It was a great job; eventually the plant relocated most of the labor “south of the border”, as it were, and laid him off. They called him up the day after they would have had to bring him back at his old salary with full benefits and pension, and offered him his old job with no benefits, no pension, and half the salary. As he told me, “I had two words for them that weren’t happy birthday.”

So the question then becomes — how do you lure talented people here, and how do you keep them? You used to be able (I almost wrote “You used to could” — I’ve been here too long) to do it with the cost of living. The IU Jacobs School of Music voice faculty became known as “the graveyard of the Met” because they could offer star singers past their prime a salary that looked small, but in the context of a cost of living that was negligible compared to what they were used to in New York. But that was 50, 60 years ago; Bloomington now has the highest cost of living in the state.

The university certainly gets people here, both in terms of faculty and students, but a chunk of those people aren’t really here to stay. If you’re here for a terminal graduate degree, it’s almost a foregone conclusion that you aren’t going to be getting a job here. That’s just not how major universities work. It might have been a different story 30-40 years ago, but not now. There are exceptions, sort of; if the completion of your PhD times out nicely with a faculty opening, then you might get a yearlong Visiting Lecturer appointment while they do a search, but you’re not realistically going to have a shot at the tenure track position. That said, there are people who come here, fall in love with the place, and decide that they’ll be Dr. Broompusher just so that they don’t have to leave. If you’re really creative you can find ways to carve out niches for yourself, but often these can turn into ways of making a living as a self-promoter.

When I was working in support staff jobs for the university, one of the things I discovered was that a lot of longtimer secretaries and such had been gradually pushed further and further out to the outlying areas of Bloomington. Basically, if you work for the university, unless you’re faculty or in the professional track of administration, you can’t really afford to live anywhere near it — partially because East Coast undergrads whose parents are used to New York and New Jersey prices have bid up the cost of housing. We’ve experienced that a bit ourselves; the apartment that we lived in our first couple of years here was about a 15-minute walk to campus, and it was in undergrad party central. It was $850/month the first year (incidentally, only $100/month less than our apartment in Seattle); it got bumped up to $950 the second year, and then they wanted to jack it up another $100 the third year. We said no, and the very next day they were showing it. They ultimately rented it for $2,000 a month.

Anyway, the point is, Bloomington seems to function as a center, at least in some ways, and they’ve created some of their own periphery. But it’s also a periphery in its own way — it’s a periphery that’s sort of a center among other peripheries. One of the results seems to be that there is a lot of socio-economic elbowing and jostling here, and a lot of cultural discomfort amongst the different strata.

So — and this really is my main point — what do you do as a church in such a situation? Well, normally, the way this seems to work out is that people on the periphery go to their churches, people in the center go to their churches, and you’ve got different cultural groups instinctively coming together at their respective churches. You certainly see that here; you’ve got Primitive Baptist communities in some of the areas a half hour away, you’ve got Campbell/Stone and Pentecostal and Baptist churches out in the outskirts of Bloomington, you’ve got the conservative Catholic parish way out in the northwest corner of town, you’ve got the moderate suburban Catholic parish less than a mile away from the campus, and you’ve got the ultra-liberal Newman Center that hosts the Dalai Lama when he’s here (“St. Paul Outside the Faith” as I’ve heard conservative Catholics call it) right on campus. On the main commercial drag through the university’s part of town, you’ve got the big Methodist church, the Episcopal church, the Disciples of Christ church. And so on.

So where do the Orthodox fit into such a picture? Well, here in Bloomington, they kind of don’t. There is one Orthodox church here, and the idea is that it serves all the Orthodox in Bloomington and can be a home for Orthodox college students and inquirers for as long as they need it. That’s a lovely idea, but how does that work out in practice given the situation that’s here? And, again, it kind of doesn’t. The problem is that All Saints has intentionally located itself in the periphery; it’s six miles from campus, two and a half miles into unincorporated county. It’s at the intersection of a couple of country roads that are neither pedestrian nor bike friendly; I used to say that if I lived across the street I’d still drive. As a result, it’s not easily accessible from the center, and in the time I was there, I saw the demographic shift substantially away from the center and more towards the rest of the periphery. And yet, it’s ostensibly the church that is serving the center, even though, for all intents and purposes, it doesn’t, and it doesn’t really want to, either. You can’t really elide all of the geographic, socio-economic, and ethnic differences all at the same time with a little shoebox church out in the middle of nowhere; maybe in a perfect world you could, but we’re talking about human beings with human foibles, and it doesn’t really work that way. Anyway, the net effect is that being close to the center allows it to function as a central location for the other peripheries, but that means that it’s a very different culture and demographic than what you would have if it were actually in the center and serving the center. So, while there’s technically an Orthodox church with a Bloomington address, there isn’t really an Orthodox church in Bloomington.

The other tricky dynamic such a community has to navigate is one of long-term vs. short-term participation. There are people at All Saints who were born and raised in Bloomington and who will be buried in the church’s cemetery. There are people who moved there for school and decided to stay. There is the small handful of students that come and go. There are people who have moved there for various reasons, seen them not work out, and simply gotten stuck (“Bloomingtoned”). There are people like me, who came thinking we’d be here 2-3 years tops, 10 years later we’re still here, but we’re still planning on being gone sometime in the very near future — long-term short-termers, in other words. How do you work out issues of leadership within that kind of dynamic? In my case, I was on the parish council, the building committee, I directed the choir and chanted, I was OCF chair for a couple of years, and so on — and for everything I was involved in, I took the stance that, however long I’m here, I’m going to participate in decision-making as though I’m going to be here in 50 years. I took an approach of trying to build things that I would want to see still standing in my grandkids’ day, in other words. But should I have done that? Did I have any business taking the long view? Or does it simply throw off the balance if a short-termer, however long-term their short-term becomes, doesn’t defer on long-term issues to the people who actually will still be there in 50 years? Does it make any sense for somebody like me to be part of the effort to build a new church, for example, when I’m not planning to be around long enough to see it built? Are people like me just creating messes that other people will have to clean up? But then, what happens when the people who are going to be around aren’t willing to be involved?

What’s the priest’s role in figuring out such questions? It seems to me that there’s a complicated problem of priests not being able to afford to tell people with energy and ideas and willingness to participate that they need to sit things out, but at the same time, if the priest is letting those people spearhead projects that he’s not willing to take on or support himself, then at what point do such people just become, effectively, cheap labor in whom the “permanent” congregation has no investment?

I’ve mused a lot on this blog about mission and outreach. Orthodox outreach is something I care very deeply about; what I keep saying is, “If we actually believe we are what we say we are, we ought to be shouting it from the rooftops.” Taking mission seriously also, it seems to me, entails taking issues of community access seriously. How do you do that in a town like Bloomington? If you build a church in the center that is first and foremost for the center, probably people in the periphery aren’t ever going to care. In that sense, All Saints really is a mission to rural southern Indiana in a way that it couldn’t be if it were better positioned to serve the population center of Bloomington. But, at the same time, the way it has positioned itself, it’s close enough to the center to count as “the Orthodox church in Bloomington” even though it effectively isn’t, which makes it very difficult for anybody else to justify getting a mission started that would intentionally serve the center. The periphery folks have their church, and they’ve got it exactly the way they want it; it’s away from everything, it’s small, it’s relatively inexpensive, it’s low-maintenance, nobody bothers them, they don’t have to worry about a proliferation of the forces they keep away from (like the university) taking over. But then, since it’s the only game in town, you have the all-too-frequent phenomenon of certain kinds of inquirers or students walking in, realizing it’s not really intended for them, and leaving. Some of them commute to Indianapolis; some of them just don’t bother considering it further.

I was almost one of those people as an inquirer, ten years ago; not gonna lie. I walked in for the first time and really wanted to walk right out (this after getting lost on the way there because the directions on the website were unclear). I tried to make it work for nine and a half years, and it sort of did, for awhile. As I said, however, I’ve seen the demographic change while I’ve been there, and while there were still vestiges of the original self-conception as “the Orthodox church for all the Orthodox in Bloomington” 10 years ago, any sense of that is completely gone now. The families that started the church have moved away or passed on; there isn’t a second generation of those folks still hanging around. As a result, the demographic has narrowed, and it has also aged and moved outward. A new generation of converts is coming in, yes, but they’re coming in from even farther away, from points further southward. We have friends there, to be sure, and our very dear godparents, but that’s a different beast than fitting in to a community. The parish has developed, and continues to develop, a very strong identity as a church for rural southern Indiana; this isn’t a bad thing on the face of it, but it means that, after nine and a half years of trying to be part of the community, we find ourselves having to commute northward now, without a local community to speak of, at exactly the time when we find ourselves most in need of it. And we’re neither the first ones to have this problem here nor the only ones currently having to navigate it.

I should say that this isn’t an issue of university snobs not wanting to rub shoulders with the townies; that should be borne out by the fact that, as I said, we tried to make it work for almost ten years, and we were involved with community life on several fronts. The issue is that, sometimes, despite everybody’s best efforts, you just don’t fit in, and eventually you’re told, “Look, this isn’t going to get any better. It’s probably time for you to stop beating your head against the wall.” Also, as I said, we’re not the only ones in this boat.

The short-term solution, for my family, is making a concerted effort to get someplace where there can be a local community. This solution may neither be easy or soon in coming, so we just have to suck it up and deal at the moment. But what’s the long-term solution for this area, and what are the lessons here for others? For all I know, the lesson is, “Don’t let uppity college punks think they have any say in how we do things because it’ll just be an exercise in frustration for everybody”, but surely there’s something more constructive.

A final observation (yes, I know that coming from me that’s as empty a promise as hearing “Let us complete our prayer to the Lord” in an Orthodox service) — All Saints has been described to me as “an experiment in seeing if you can establish an Orthodox church somewhere where there have never been the usual reasons for having one”; that is, where there haven’t been groups of cradles who have established parishes. Well, to the extent that it has been successful, I’d argue it has done so by creating its own “ethnicity” that you belong to or you don’t. Maybe that’s what you have to do; I don’t know. The thing that’s very curious to me is that there have always been big groups of people here of ostensibly Orthodox heritage — Greeks and Russians in particular. I say sometimes that there is a big Greek community in Bloomington; they’ve started a church (the community that became All Saints was originally a group of Greeks and Arabs) and they’ve started several restaurants, but they’ve never started either a Greek church or a Greek restaurant. (Semi-untrue now — there’s Topo’s 403, but it’s less of a “Greek restaurant” and more of an upscale trendy place that happens to be somewhat Mediterranean-influenced.) There was a rembetiki concert here a couple of years ago that got around 200-250 of the Greeks in the area all under one roof; it made me very sad to hear one of them say, “It’s so nice to see everybody in one place. Maybe someday one of us will start a restaurant and we can all see each other there.” Also, the Russian Church Abroad had a mission here in the 1950s, but for one reason or another they never quite managed to keep it together. They fell apart in the ’60s, sort of re-integrated in the ’70s, and then fell apart for good in the ’80s. They started out with a building in the center of Bloomington and then moved out to the periphery, buying an auto garage out in the county. Then, as somebody told me irony-free, “the big money went with Antioch and we had to shut our doors.” (The infamous “Indiana listserv” was run by one of their minor clergy, who is now a priest in one of the “continuing” Russian Orthodox groups who didn’t like that ROCOR made nice with Moscow.) The people have been here (and are here); they just don’t seem to feel that they have any skin in the game — which, again, seems to me to be a problem with the periphery gathering in the center while simultaneously ignoring the center.

I don’t know what the answer is, and I don’t think I’ll be here long enough to see how it gets answered (noting that I’ve been wrong about such things before), but it seems to me that there’s an object lesson here. I’m just not sure what it is.

Two weeks and a day until exams. Please pray for me.