In a discussion with a Calvinist friend (and to be fair, I don’t know that he himself identifies as a Calvinist, but his church certainly identifies as “Reformed” with lots of appeals to Calvin) about something else recently, one of our points of disagreement on the issue at hand was determined to be rooted in doctrinal differences. In this case, it was a matter of whether or not the Gospel is principally a textual phenomenon. I said that it is not; the Gospel is Christ resurrected in the flesh, trampling down death and redeeming fallen Adam — that is, the Truth of our faith is a Person whom we know and with whom we have fellowship, not a set of texts we read. The texts are a way we know about Him, and a way He is proclaimed in the context of the worshipping body, but those texts aren’t the only way or even the principal way we know about Him or proclaim Him. My friend’s response was to say, you’re right, this is a doctrinal dispute that’s older than we are, but needless to say, I unabashedly adhere to sola Scriptura and believe Scripture teaches it.

A different conversation with an Orthodox person about a completely different matter also touched on the question of textuality, in this case whether or not liturgy, as understood by the Orthodox, is a chiefly textual experience. To this person, the answer was without question yes; everything in our services more or less expresses a set of texts, and anything that obscures those texts need to be reconsidered. My thoughts on the matter were that the Divine Liturgy is chiefly the celebration of the Eucharist — that is, communion with God — not a proclamation of text. While there are texts that are proclaimed, they are done so in the context of other sensory experiences — incense, icons, singing, movement, and so on. Yes, this person replied, but the celebration of the Eucharist is preceded by the parts of the service intended to prepare us to receive it, which means prayers that we’re supposed to say, and while we do adorn the texts with things like incense, those seem to have only become important as we’ve gotten away from understanding the Liturgy as textual. Part of my problem, as I told this person, is that sounds a little close to sola Scriptura for me; no, he replied, sola Scriptura is a doctrinal dispute between Protestants and Catholics that doesn’t have anything to do with us. Hm.

By contrast to both of those discussions, another friend was telling me about a paper he’s having to write for an ethics class. His professor is big on a threefold model of “doing, thinking, and knowing”, and evidently the model that gets used is that of romantic relationships — dating -> doing, engagement -> thinking, marriage -> knowing. So, my friend is looking at how this model might apply to textures of Byzantine chant. He’s arguing that things like psalm verses, refrains, petitions, liturgical dialogue, and so on constitute “doing”, stichera and troparia (to name a few) are “thinking”, and then the melismatic textures are “knowing”. He singled out kratemata and terirem (basically musical meditations on nonsense syllables) as, in this model, being the ultimate form of “knowing”, saying that if hesychasm is our ideal form of prayer, then these represent the musical equivalent. I was reminded of this passage from St. Augustine’s commentary on Ps. 100:

The one who sings a jubilus [qui iubilat] does not speak with words, but it is a certain sound of joy without words: it is the voice indeed of a soul exhilarated with joy, expressing to the extent possible love but not encompassing sentiment. A man rejoicing in his own exultation, after certain words which are not able to be spoken or understood, bursts forth into such a voice of exultation without words; so that it appears that he indeed rejoices with his own voice, but as though filled with too much joy, he is not able to express with words that in which he rejoices.

I’ll note that I’ve heard qui iubilat argued to mean “the one singing a jubilus” (that is, the melismatic ending to the Alleluia in the Mass); I’ve also heard it argued that this understanding must be anachronistic, and that is simply means “he who jubilates”. The former is what I was taught in music history, so I’ll stick with it for now. In any event, whatever qui iubilat means, this “sound of joy without words” seemed to be very much what my friend was getting at with the “knowing” part of the model.

Finally, I recently encountered this passage from a 1923 essay by Pavel Novgorodtsev titled “The Essence of the Russian Orthodox Consciousness”:

When… Protestant writers reproach the Orthodox Church for not developing sufficiently the practice of spiritual exhortation in its church services, for having little concern for the moral superiority of its flock, then here… misunderstanding continues. For the Protestant in his church service, between the bare walls of his temple, the chief thing is to listen well to the moralizing teaching, to do the expected psalm singing and prayers, which have as their goal the same moral concentration and self-purification. The chief thing here is human influence and personal introspection. On the contrary, for the Orthodox the main thing in the Church service is the action of divine grace on the believers, their communion with divine grace. Here it is not human influence that is determinate but divine action; the goal here is not simple moral education but mystical unity with God. The beneficent force of the Eucharist and liturgical religious rites, in which the grace of God mysteriously descends upon those who pray — this is the highest focus of the church services and prayerful exhortations. The cry of the holy servant [that is, the priest celebrating the Eucharist] “May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God the Father and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all” summons the gifts of divine grace on all present at the liturgy[.] (collected in A Revolution of the Spirit: Crisis of Value in Russia, 1890-1924, ed. Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal and Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak)

How to put all of this together? To come back to the conversation with my Calvinist friend, I was really struck by how he described himself as “unabashedly” adhering to sola Scriptura. I’m pretty sure he didn’t mean this, but in thinking about it, it seemed that it could be understood as him thinking that the main reason one might not adhere to sola Scriptura is because they are “abashed” — that is, ashamed of Scripture. This would be suggested by something that he said, that we have to be willing to proclaim all the truth of Scripture — not just the easy, warm and fuzzy parts, but also the “gnarly” (his word) bits that are hard to reconcile with where the world is at right now.

In any event, I don’t adhere to sola Scriptura, and I unabashedly don’t adhere to sola Scriptura, but I don’t unabashedly not adhere to sola Scriptura because I’m ashamed of Scripture. Now, here’s the problem — how does one restate that positively?

The arguments about sola Scriptura are centuries old, and no blog post I could possibly write in between spurts of exam reading is going to resolve that dispute, so I’m not going to bother trying. Here are some things that I think I can say about the experience of an Orthodox Christian with respect to Scripture:

- The principal experience of Scripture for an Orthodox Christian is hearing it proclaimed in the context of the worshipping body. That’s not to say that we don’t ever read it on our own, just that the normative way it is transmitted and received is that it is heard in the context of corporate worship. That includes the Epistle and Gospel readings in the Divine Liturgy, but it also includes Old Testament readings at Vespers, Gospel readings at Matins, and Psalms at every service. Another way to put this is that the Gospel, Epistles, Psalter, and Prophets are books written by the Church, organized and edited by the Church for the Church, and done so for the Church’s use. If this seems a bizarre way to think of the Bible, well, I refer you to Harold O. J. Brown, late of the faculty of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, who noted once that “there is no way to make the New Testament older than the church” (“Proclamation and Preservation: The Necessity and Temptations of Church Traditions”, Reclaiming the Great Tradition, Intervarsity Press, 1996).

- (As a side note, I’ll say that somebody close to me recently bought an audiobook version of the Bible. “It’s really fascinating what you get out of it hearing it out loud rather than just reading it on your own,” this person said to me. “Have you ever heard it that way?” I gently suggested to this person that this is not exactly news in Orthodox circles.)

- The hearing of Scripture in the context of the Liturgy is one of many elements in support of the celebration and reception of the Eucharist, the Body and Blood of Christ. The Eucharist is not in support or an expression of Scripture; it may be the Body and Blood of the incarnate Word, but that’s not the same thing as saying that it’s chiefly about words.

- Scripture is not in conflict with Tradition. Scripture is the component of Tradition that has been passed down through the written witness of the Apostles, the Evangelists, and Prophets. We have knowledge of what Scripture is because the Church was able, by means of Tradition, to evaluate the various writings claiming status as Scripture.

- The Truth that we proclaim is not a set of writings, but a Person. The Gospel is that the Christ, the Son of the Living God, having been crucified in the flesh, rose from the dead and trampled down death by means of death itself. Scripture is one of the ways that this is witnessed to and proclaimed, but it is neither the only way nor even the chief way. One of the chief ways, yes.

- The Divine Liturgy, the celebration of the Eucharist, is itself not principally a textual experience. It is an experience of heaven on earth, communion with the Living God, a foretaste of the heavenly kingdom. There are many modalities of sensory experience that are used to present this image of heaven; hearing and sight are among them, but one hears many other things besides just the plain words of Scripture in the context of our worship, and while one may see things that invoke certain Scriptural images (there is a distinct relationship between what one sees going on at the altar and the description of heavenly worship in the Apocalypse of St. John, for example), one rarely sees the words of Scripture in a service as such (unless it is one’s liturgical function to proclaim Scripture). Sensory experience as a way of knowing God has a long Christian tradition; I refer the reader to Susan Ashbrook Harvey’s study of the sense of smell in the late antique Christian East, Scenting Salvation, as a place to start on this.

- None of this is to discount, devalue, displace, diminish, disobey, marginalize, or minimize Scripture. No, indeed; the point is honor Scripture in its proper place — to “hold fast to the traditions received from [the Apostles], whether by [their] word or [their] epistle” (2 Thess 2:15), and to hold the high view of the Church that we are to have, as witnessed to by Scripture — that the Church is “the pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15).

As I said at the outset, my words — which sound an awful lot like a thousand other similar such things written by Orthodox Christians — aren’t going to resolve the long-held disagreements about this, so I’m not going to pretend they have any chance of doing so. The point is, what’s the positive thing that an Orthodox Christian can affirm so that we’re not just saying, “I don’t adhere to sola Scriptura“? Maybe ὅλη παράδοσις — “whole Tradition” (or “the whole of Holy Tradition”? Try saying that five times fast)? I guess it’s not found in Scripture in so many words, but it’s doing neither better nor worse than sola Scriptura on that front.

Let’s try that, then. I unabashedly adhere to ὅλη παράδοσις, Tradition in its fullness, and I believe that Scripture teaches it.

Today, if I were to find myself in a similar exchange, I would still have the person read Florovsky, but I would give him

Today, if I were to find myself in a similar exchange, I would still have the person read Florovsky, but I would give him  As I announced back in May

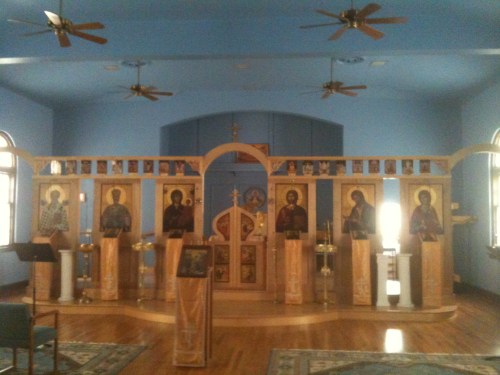

As I announced back in May I will also note that they’ve made it a point to first and foremost treat the building as a place of worship, and they have prioritized their efforts accordingly. I am familiar with phased church building projects where the approach is, “Well, people come to church for services, but they stay for everything else a church does, so best to build something that one can get by in for worship and that maximizes the ability to do all of the ancillary things. Then you’ll grow faster and can build the temple down the road.” I humbly submit that this approach doesn’t really work, at least not from what I’ve seen. The Church is first and foremost a worshipping body, not a coffee-drinking body, and when you put what is supposed to be our first priority in second place so that the men’s group has somewhere to meet, I think people sense that. Worse, from what I’ve seen, the ways you have to rethink your liturgical practice in a setting you’ve built only for the bare minimum of accommodation have a nasty tendency to become permanent. This means that if the day ever comes where you get to build the permanent temple, you’re already wondering, “Well, why do we need [X component of ecclesiastical architecture] anyway, when it adds another $250k to the price and we’ve learned how to get along just fine without it in our existing space?” By contrast, St. Nicholas has prioritized the liturgical function of the building over secondary activities, and it shows with the care they’ve put into their furnishings. They’ve clearly been able to do a lot with what resources they have, and they’ve also shown a lot of forethought in leaving the walls white so that they can be frescoed later.

I will also note that they’ve made it a point to first and foremost treat the building as a place of worship, and they have prioritized their efforts accordingly. I am familiar with phased church building projects where the approach is, “Well, people come to church for services, but they stay for everything else a church does, so best to build something that one can get by in for worship and that maximizes the ability to do all of the ancillary things. Then you’ll grow faster and can build the temple down the road.” I humbly submit that this approach doesn’t really work, at least not from what I’ve seen. The Church is first and foremost a worshipping body, not a coffee-drinking body, and when you put what is supposed to be our first priority in second place so that the men’s group has somewhere to meet, I think people sense that. Worse, from what I’ve seen, the ways you have to rethink your liturgical practice in a setting you’ve built only for the bare minimum of accommodation have a nasty tendency to become permanent. This means that if the day ever comes where you get to build the permanent temple, you’re already wondering, “Well, why do we need [X component of ecclesiastical architecture] anyway, when it adds another $250k to the price and we’ve learned how to get along just fine without it in our existing space?” By contrast, St. Nicholas has prioritized the liturgical function of the building over secondary activities, and it shows with the care they’ve put into their furnishings. They’ve clearly been able to do a lot with what resources they have, and they’ve also shown a lot of forethought in leaving the walls white so that they can be frescoed later.

I got home from the

I got home from the  So,

So,